For personal reasons this year I decided not to have an official "Ant Together." The short story is that my grandfather unexpectedly passed away during the peak month that we would have had one. I found myself in this odd state of mine where I just wanted to skip everything required of me and not volunteer for certain family obligations... thus it stood to reason that I shouldn't be doing other things either such as holding events.

Though the truth is as much as I like to promote the New Jersey Ant Together as a big annual thing, it's never escaped being a simple hiking trip with like minded individuals. And maybe it should stay as a simple get together in future.

I did manage to get a trip in thanks to my friend Matt coming back for a visit. He's attended every Ant Together I've ever done so it was good to get some in while he was back home. Our hunting ground of choice was the Rancocas Nature Center where we held our first one.

This was not our most productive trip, mostly owing to the fact that I forgot my shovel (Doh!), but we still had fun. Our first visit there five years ago we had come across colonies of Polyergus, Stigmatomma, and Strumigenys which was pretty good for our first time! Polyergus are specialist slave making ants of the common Formica genus, that are only found in certain fields. Stigmatomma are a type of "Dracula Ant" which specializes on hunting down centipedes for food. The term Dracula Ant comes from their habit of feeding on their own larva through non-lethal cutting. Strumigenys are cryptic, often hard to find, specialist on soft bodied arthropods... basically miniature Trap-Jaw Ants. None of which we found on our trip owing to the fact that it was very late in the summer.

Formica incerta, very similar looking to Formica pallidefulva, differing primarily by the amount of facial hair. The two species often live in the same fields together and prefer not so lush lawn or scrub habitats. Colonies tend to be small typically around 2,000 to 10,000 ants. Queen number varies with these two species, I believe because some colonies are in the habit of allowing new queens to return to the nest after mating. The colonies then divide after that. It's likely this behavior came about from the presence of other slave making Formica and Polyergus species, perhaps even becoming more common when these threats are around.

Camponotus pennsylvanicus The Eastern Black Carpenter Ant, is easily identified by its large size, ~8 to 15mm. They are solid black color in color, though sometimes the legs with hue dark brown or red, more so in queens than workers. Also they have large amounts of hair on the gaster (abdomen), that's usually brown or gray in color. Colonies are strictly Monogyne/Oligegyne where they only tolerate one queen at a time; the Oligegyne comes from the fact that occasionally colonies have two egg laying queens in them... this is a temporary situation at best and likely comes from a situation where a new queen was brought back into the nest on accident. The new queen is "safe" as long as she's not in the same satellite nest as the mother queen of the colony. These situations usually resolve themselves each winter when colonies reduce the number of satellite nests retreating into one or two locations.

Crematogaster cf. cerasi. This likely is Crematogaster cerasi from their habit of sometimes building shed-like structures over the aphids and leaf hoppers they tend. Crematogaster species otherwise tend to be difficult to identify because of how similar most of them look and needing to count the number of hairs on parts of the body from multiple workers to get a range. This colony likely only has one queen but grows to be enormous in size. Locally they're known for having extensive foraging trails and satellite nests established basically in any dead wood structure or hollow cavity they can find. Despite this they're not really a structural pest.

The genus Crematogaster is easily identified because their waste segment connects to the upper half of the gaster, where as every other ant genus in the world connects to the lower half, or to both with a wide surface area. Their gaster is also considered "heart-shaped." The reason for this upper connection to the gaster is so they can more easily flick venom onto enemies or "sting" venom in an overhead like action as a scorpion would go to sting. Their stinger is said to be soft and flexible, like a hair so really they're not so much injecting venom as painting it on.

Aphaenogaster is a true genus of scavengers in the forests of the North East. Now that it's late summer the Dog Days Cicada's are dropping like flies and the ants are cashing in. It's been said that ants keep the forest floor clear of dead insects and it's uncommon for a carcass to go more than 5 minutes without being discovered by an ant.

Discovery is one thing though. Dismantling and hauling it away might take a day or two. These were ripping at the soft parts first and eventually managed to remove the legs. I did not stay to watch anything more.

While we didn't come across any slave making Polyergus, we did chance upon a colony of slave making Formica. This is either Formica pergandei or rubicunda. I didn't collect any specimens, so we'll likely never know what they are unless I go back sometime. This doesn't matter much though as both species tend to live exactly the same way. F. pergandei has 1 - 4 hairs under the head, while F. rubicunda always has 4. F. rubicunda is also more in the habit of having dark patches on the head and thorax. There are other slight differences but this is the kind of stuff that taxonomists nit pick about for hard identifications.

This is a good photo of the waste segment, looking head on, which is the light orange heart-shaped part before the black gaster. But this is also a bad photo of the "clypeal notch" which is the front section on the head between the mandibles. Trust me there is a notch there; it's visible in other photos I took of these ants. Unfortunately none of these were good enough photos I felt worth uploading and showing. I mention the notch because Formica is the largest ant genus in North America and it's the defining characteristic that narrows it down to those two species.

Members of the Sanguinae

group of Formica HAVE to have host ants within the colony to do the

work for them. They are obligated slave makers. Other species of Formica

found in the Exsecta, Rufa, and Microgyna groups might use host

colonies to found new nests, but after that host species are no longer

needed. In fact the Formica exesectoides mounds we like to visit

in Turkey Swamp Park rarely use host species. They've move beyond the

need for them, allowing new queens from their own colony back into the

nest to form a massive super colony within the forest.

These do require slaves though and we chanced upon, I believe starting out on a raid.

They would pull up individuals of their own species out of the nest and then began running along a trail to a host colony I believe to be either Formica fusca or subsericea. They would then run into the nest, grab a cocoon of one of their hosts and bring it back. None of which I got any good photos of :(

Showing posts with label Aphaenogaster. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Aphaenogaster. Show all posts

Tuesday, September 20, 2016

Saturday, July 30, 2016

Some Uncommon Ants In My Yard

While trying to photograph Aphaenogaster dispersing Trillium seeds I chanced upon a few unexpected surprises. The only colony I was able to find actively foraging happened to be in an old stump, a former Norway Maple we had had cut down many years ago. To set the scene properly this was in the shade of an Eastern Redbud Tree and the stump is now used as a perch for a Mason Bee box as well as a stone dish we use as a bird's bath. Naturally we flush out the water every day or so to keep the mosquito larva down and the stump has been getting soaked for many years. The result seems to be idea for a surprising amount of ant diversity.

The stump is absolutely teaming with decomposing arthropods. Here an Acorn Ant, Temnothorax curvispinosus, has found one. Small soft bodied creatures such as this, especially ones smaller than the ants themselves make excellent ant food. It's likely several colonies of Acorn Ants are also nesting within the log.

Here a Strumigenys pergandei has also caught something, I believe it's a spring tail. These ants are rarely seen because the only nest in shaded places that are "cold and damp." Cold refers to when they nest in soil, usually under a rotting log. Generally the soil will be cool to the touch, even in summer. They hunt and forage in rotting wood and leaf litter, often where decomposing insects and arthropods are abundant enough to have turned much of the dead plant matter into soil. Supposedly the yellowish structure on their waist segments, as well as the petal-like structures on their head and body are to help camouflage them from prey items.

This is an awful shot of a Proceratium silaceum but they were there too. Even more cryptic than Pyramica, they have a front facing stinger on the end of their gaster (abdomen) so they can sting prey that's in front of them, in tight closed spaces, as opposed to having to turn around. They're worth a google image search to get the idea.

It's nice knowing these uncommon ants can still be found in my yard, because this is the first time in several years that I've seen either in my yard. Now I know where to look!

The stump is absolutely teaming with decomposing arthropods. Here an Acorn Ant, Temnothorax curvispinosus, has found one. Small soft bodied creatures such as this, especially ones smaller than the ants themselves make excellent ant food. It's likely several colonies of Acorn Ants are also nesting within the log.

Here a Strumigenys pergandei has also caught something, I believe it's a spring tail. These ants are rarely seen because the only nest in shaded places that are "cold and damp." Cold refers to when they nest in soil, usually under a rotting log. Generally the soil will be cool to the touch, even in summer. They hunt and forage in rotting wood and leaf litter, often where decomposing insects and arthropods are abundant enough to have turned much of the dead plant matter into soil. Supposedly the yellowish structure on their waist segments, as well as the petal-like structures on their head and body are to help camouflage them from prey items.

This is an awful shot of a Proceratium silaceum but they were there too. Even more cryptic than Pyramica, they have a front facing stinger on the end of their gaster (abdomen) so they can sting prey that's in front of them, in tight closed spaces, as opposed to having to turn around. They're worth a google image search to get the idea.

It's nice knowing these uncommon ants can still be found in my yard, because this is the first time in several years that I've seen either in my yard. Now I know where to look!

Sunday, May 24, 2015

Some Early Myrmecochory Action

I so rarely get to see my specimens of Twinleaf, Jeffersonia diphylla, all flowering at once, let alone be pollinated by one another to see the seedpods. Normally the pods don't grow bigger than a nickle and shrivel up with nonviable seed inside. Today though I came across a fairly large seedpod. I reached down to see if it was soft enough to harvest and the darn thing broke right off the stem on me. Worst of all, the seeds weren't ready yet.... Waste not, want not.

Twinleaf disperses its seeds with aid of ants. Normally the seeds are rock hard and brown very much like unpopped popcorn. These had their little bit of elaiosome formed but the seeds were soft and green, like peas or green beans. The ants didn't seem to mind this and carried them off all the same.

The elaiosome is what's treasured by the ants but with the seeds still soft it's likely they'll be eaten too. This is just as well though. I doubt they would have grown in this early state anyway.

The ants here are Aphaenogaster rudis, which is actually a complex of several species. DNA analysis to count the number of chromosomes is required for a true species ID but overall they're the same. The species names are more or less scientific codes instead of Latin names, so the blanket term A. rudis works fine. They're all commonly found in woodlands across North America, they all nesting in soil and sometimes rotten wood in contact to the soil. They all form colonies with populations ranging from 2,000 - 12,000 ants. Nests are small and move around on occasion, making them ideal seed dispersers, along with their size.

Ideally the seeds would be rock hard and either discarded in the nest, or hauled out to the waste or midden pile where it would be buried in dead insects and other discarded seed husks anyway. Often plant seeds like this require two winters to germinate, where it's more likely the colony of ants has moved on, and or the garbage heap has decomposed into plant fertilizer. Some plants such as Trilliums emit a terrible odor when they germinate which likely helps encourage the ant colony to move along.

The ants find nourishment everywhere they can, even among the seedpod itself. If the ants didn't come along to clean out the seeds, rodents, birds, and wasps would have. Rodents and birds love eating the seeds. Wasps go for the elaiosome just like the ants, but are unlikely candidates for seed dispersal. They may drop them on the surface for birds and rodents to find, or bury them too deep within the earth, or the seed could end up within the dead branch of a tree.

One plant that was right on time was the Woodland Poppy, Stylophorum diphyllum. The same idea of seed dispersal applies, however I can't get it out of my head how much the elaiosome to this plant resembles ant brood. It just looks like clusters of eggs and larva, which ants are more than happy to eat, especially if it doesn't belong to them.

The seeds, being ripe, are rock hard and firmly attached to the elaiosome packet. I have trouble removing it and I'm a human! It's unlikely the ants will be able to chew them into dust or "ant bread" so they'll be discarded within the nest and in a few years I'll likely have a patch of woodland poppy growing here.

Where this strategy of seed dispersal can go wrong though is when the wrong sort of ant finds the seed. This is an Acorn Ant known as Temnothorax curvispinosus. They're adorably tiny, with small colonies of ~200 workers that all fit right inside a hollow acorn, hollow plant stems, or dead plant matter. Not only do they nest in the wrong sort medium for starting seeds, but also the workers are too small to carry the seeds off. They're more likely to just recruit more workers from the colony and deal with the elaiosome where they found it, and the seed is simply left where it was beneath the parent plant.

As a disclaimer I will admit all of these photos were staged to a point. You'll notice I just opened the seedpods and spilled them on a stepping stone where an Aphaenogaster rudis colony happens to nest. I just don't have the time to wait for this to happen naturally in my yard, but trust me it does. There are plenty of Woodland Poppy plants with open seedpods on them right now that have spilled their seeds in the garden. I typically find Tapinoma sessile and Crematogaster cerasi stealing the elaiosome from the seeds where they fell and don't disperse them. The occasional Aphaenogaster forager does find a few though and bring them back to the colony. Since they've been self seeding in my yard for the past three years now I've been finding Woodland Poppies coming up in places where ant colonies tend to nest, and or have been dragged away from the parent plant a short ways at least. Sometimes the ant carrying the seed home gives up or gets disturbed by a spider or something.

Turkey Corn, Dicentra eximia, will likely be the next plant who's seeds do this to ripen in my garden... sadly I missed my chance with Hepatica this year, but they seem okay about germinating where they fall anyhow. So though a plant uses this strategy to disperse its seeds, it's not always required for success, simply a way to give them a leg up.

Twinleaf disperses its seeds with aid of ants. Normally the seeds are rock hard and brown very much like unpopped popcorn. These had their little bit of elaiosome formed but the seeds were soft and green, like peas or green beans. The ants didn't seem to mind this and carried them off all the same.

The elaiosome is what's treasured by the ants but with the seeds still soft it's likely they'll be eaten too. This is just as well though. I doubt they would have grown in this early state anyway.

The ants here are Aphaenogaster rudis, which is actually a complex of several species. DNA analysis to count the number of chromosomes is required for a true species ID but overall they're the same. The species names are more or less scientific codes instead of Latin names, so the blanket term A. rudis works fine. They're all commonly found in woodlands across North America, they all nesting in soil and sometimes rotten wood in contact to the soil. They all form colonies with populations ranging from 2,000 - 12,000 ants. Nests are small and move around on occasion, making them ideal seed dispersers, along with their size.

Ideally the seeds would be rock hard and either discarded in the nest, or hauled out to the waste or midden pile where it would be buried in dead insects and other discarded seed husks anyway. Often plant seeds like this require two winters to germinate, where it's more likely the colony of ants has moved on, and or the garbage heap has decomposed into plant fertilizer. Some plants such as Trilliums emit a terrible odor when they germinate which likely helps encourage the ant colony to move along.

The ants find nourishment everywhere they can, even among the seedpod itself. If the ants didn't come along to clean out the seeds, rodents, birds, and wasps would have. Rodents and birds love eating the seeds. Wasps go for the elaiosome just like the ants, but are unlikely candidates for seed dispersal. They may drop them on the surface for birds and rodents to find, or bury them too deep within the earth, or the seed could end up within the dead branch of a tree.

One plant that was right on time was the Woodland Poppy, Stylophorum diphyllum. The same idea of seed dispersal applies, however I can't get it out of my head how much the elaiosome to this plant resembles ant brood. It just looks like clusters of eggs and larva, which ants are more than happy to eat, especially if it doesn't belong to them.

The seeds, being ripe, are rock hard and firmly attached to the elaiosome packet. I have trouble removing it and I'm a human! It's unlikely the ants will be able to chew them into dust or "ant bread" so they'll be discarded within the nest and in a few years I'll likely have a patch of woodland poppy growing here.

Where this strategy of seed dispersal can go wrong though is when the wrong sort of ant finds the seed. This is an Acorn Ant known as Temnothorax curvispinosus. They're adorably tiny, with small colonies of ~200 workers that all fit right inside a hollow acorn, hollow plant stems, or dead plant matter. Not only do they nest in the wrong sort medium for starting seeds, but also the workers are too small to carry the seeds off. They're more likely to just recruit more workers from the colony and deal with the elaiosome where they found it, and the seed is simply left where it was beneath the parent plant.

As a disclaimer I will admit all of these photos were staged to a point. You'll notice I just opened the seedpods and spilled them on a stepping stone where an Aphaenogaster rudis colony happens to nest. I just don't have the time to wait for this to happen naturally in my yard, but trust me it does. There are plenty of Woodland Poppy plants with open seedpods on them right now that have spilled their seeds in the garden. I typically find Tapinoma sessile and Crematogaster cerasi stealing the elaiosome from the seeds where they fell and don't disperse them. The occasional Aphaenogaster forager does find a few though and bring them back to the colony. Since they've been self seeding in my yard for the past three years now I've been finding Woodland Poppies coming up in places where ant colonies tend to nest, and or have been dragged away from the parent plant a short ways at least. Sometimes the ant carrying the seed home gives up or gets disturbed by a spider or something.

Turkey Corn, Dicentra eximia, will likely be the next plant who's seeds do this to ripen in my garden... sadly I missed my chance with Hepatica this year, but they seem okay about germinating where they fall anyhow. So though a plant uses this strategy to disperse its seeds, it's not always required for success, simply a way to give them a leg up.

Wednesday, September 3, 2014

Arizona: Meeting Ray Mendez

An incredible highlight of the Ants of the Southwest course was a visit to Ray Mendez's house.

Here is his house, and that's the view he gets to wake up to every morning.

It's Pogonomyrmex adjacent.

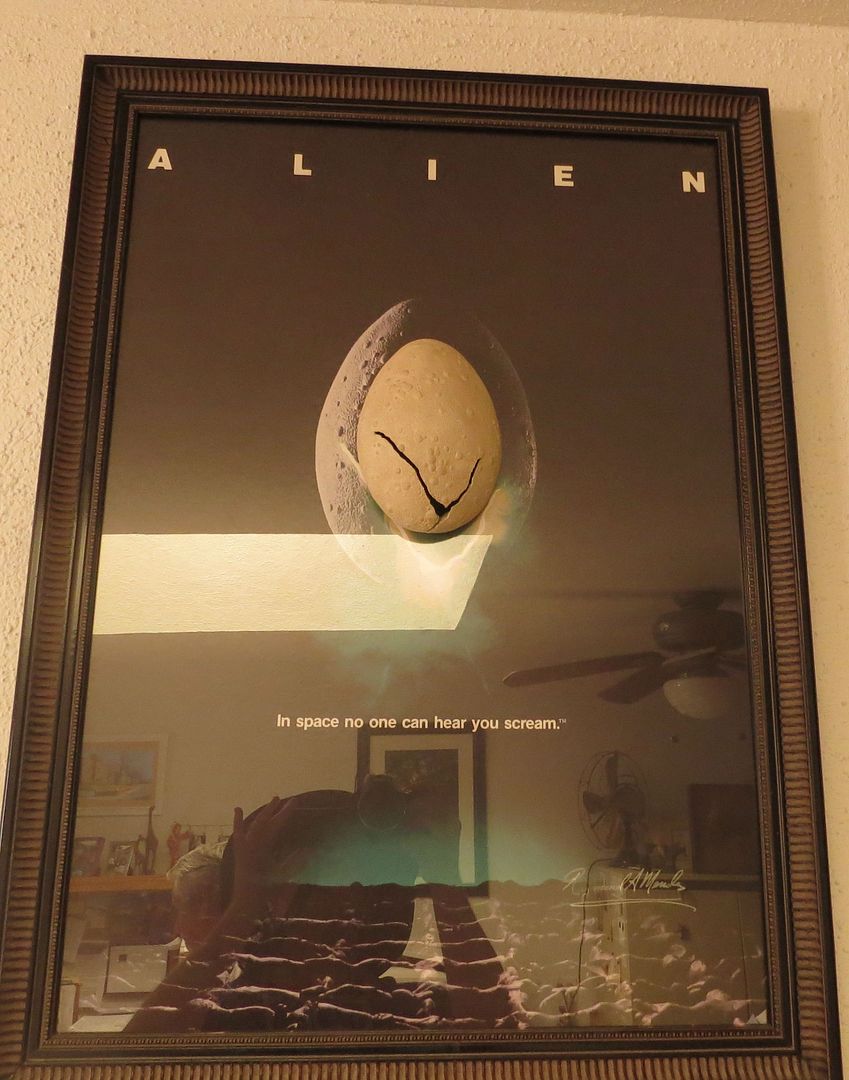

Inside he has some interesting artwork hanging from the ceiling. But you might be asking, what makes Ray so special?

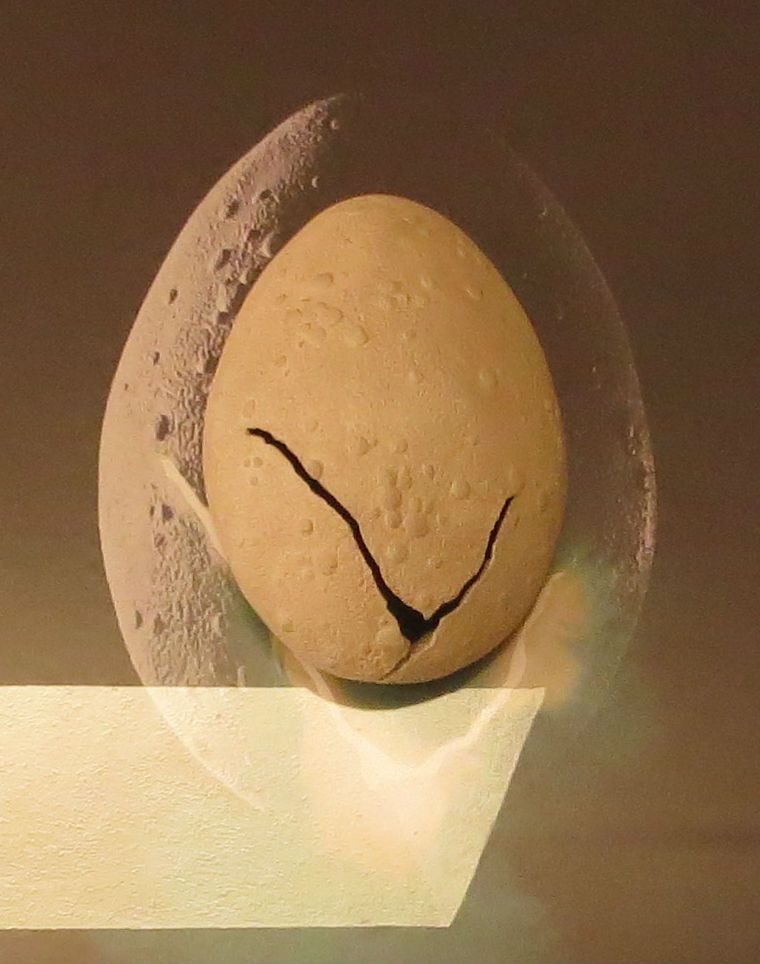

He made the alien egg and worked on some of the effects for the movie "Alien." He also helped inspired what has to be the greatest tagline for a horror movie in cinema history. "In space no one can hear you scream."

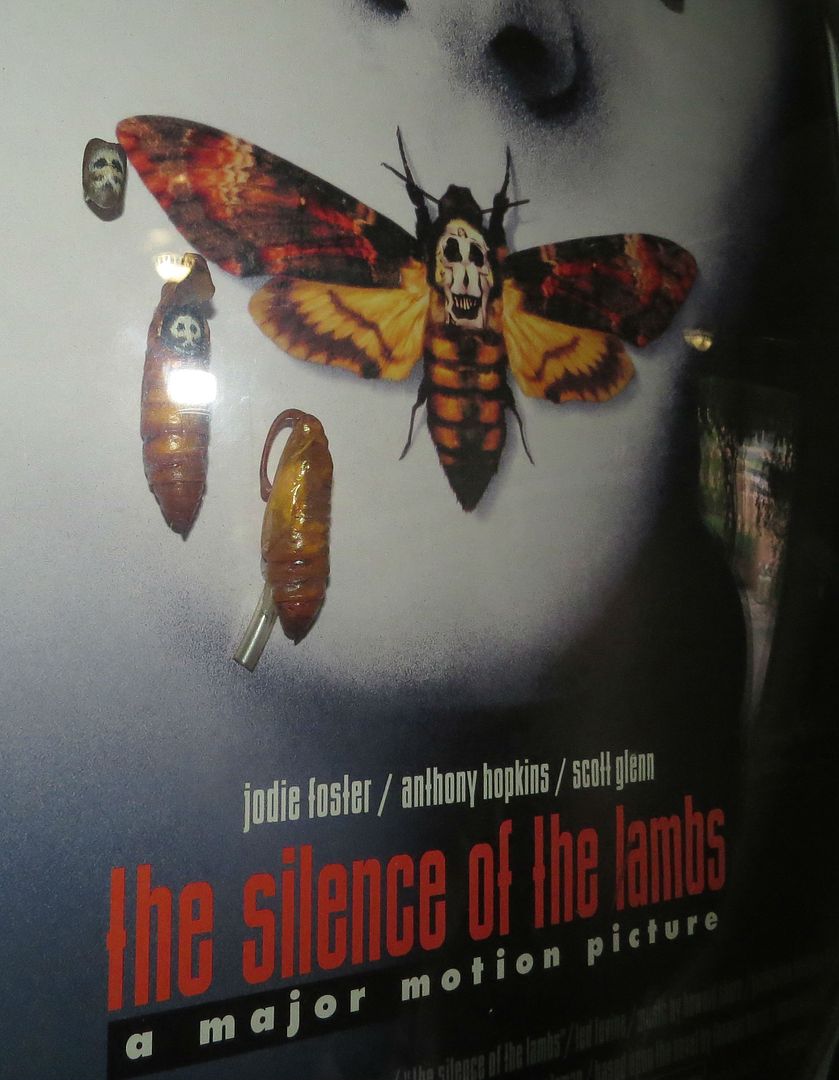

He did the bug work for the film, "Silence of the Lambs."

It's actually a cockroach done up to be a moth.

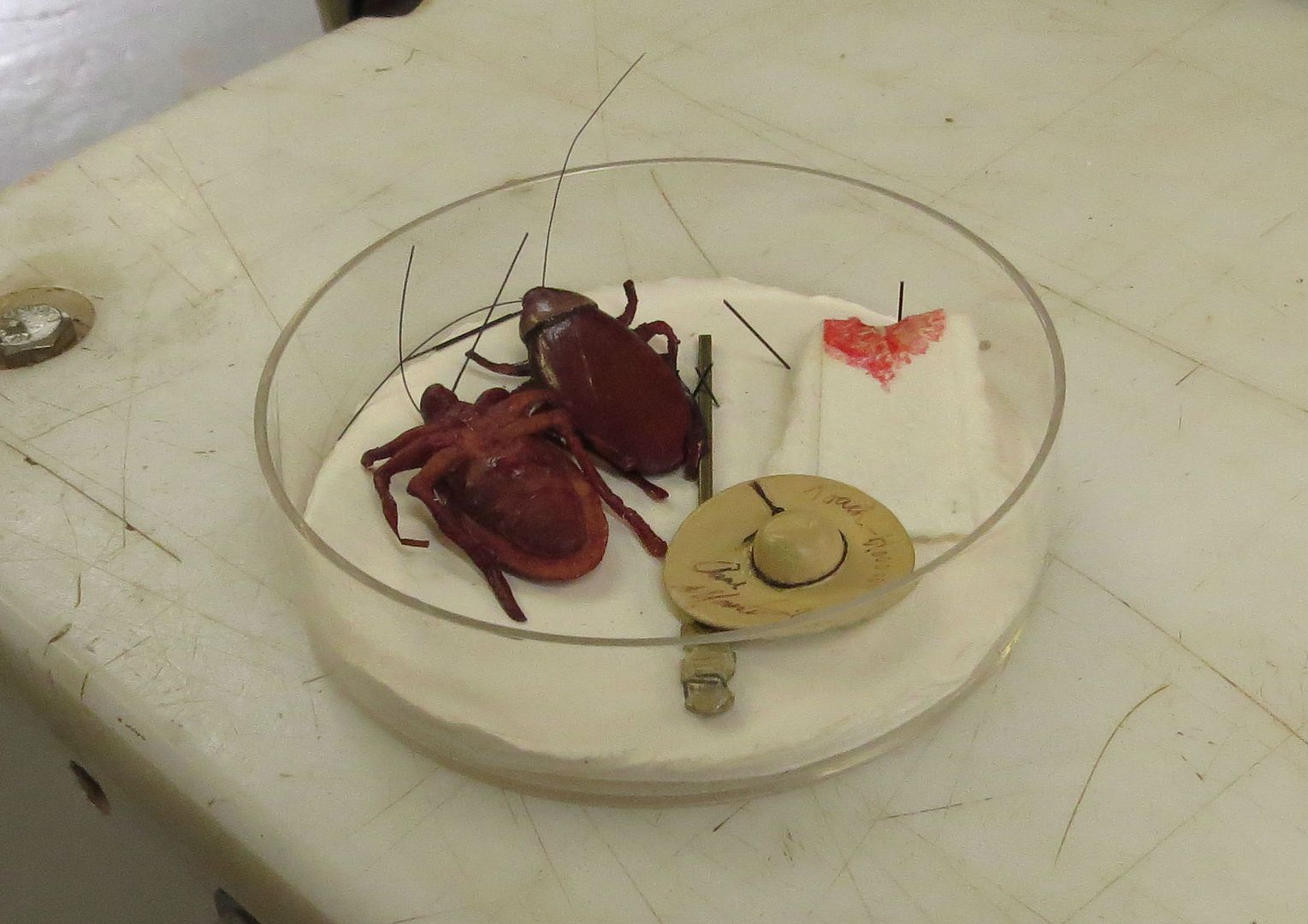

He was the roach wrangler to the film "Joe's Apartment," which is admittedly a bad movie but the stories he has to tell about making it sound like they had an awesome time filming. (They got to pump a few thousand roaches up a girl's dress.)

His portfolio includes a smattering of advertising campaigns.

Here Ray bestows his wisdom to the Ants of the Southwest class in his workshop.

He also builds professional grade setups for museum exhibits and sets used for documentations to film. Pictured above is an above ground scene used in "Empire of the Desert Ants" a few years ago. It's hard to see but there are two openings leading down beneath the setup. Two different colonies can be hooked up here and their interactions filmed. For the documentary they filmed both the demise of the main colony, as well as the main colony conquering anther nest all at the same time. Because the ants of both colonies look identical you don't know that you're looking at two separate colonies.

For these setups, whole nests can be attached underneath. This allows camera men to film the workers right as they emerge from the hole. The whole setup as well as the disk can also be buried in the ground and blended in with the surrounding soil. This way filmmakers can have an ant nest in an ideal location for both lighting, background, and ambiance.

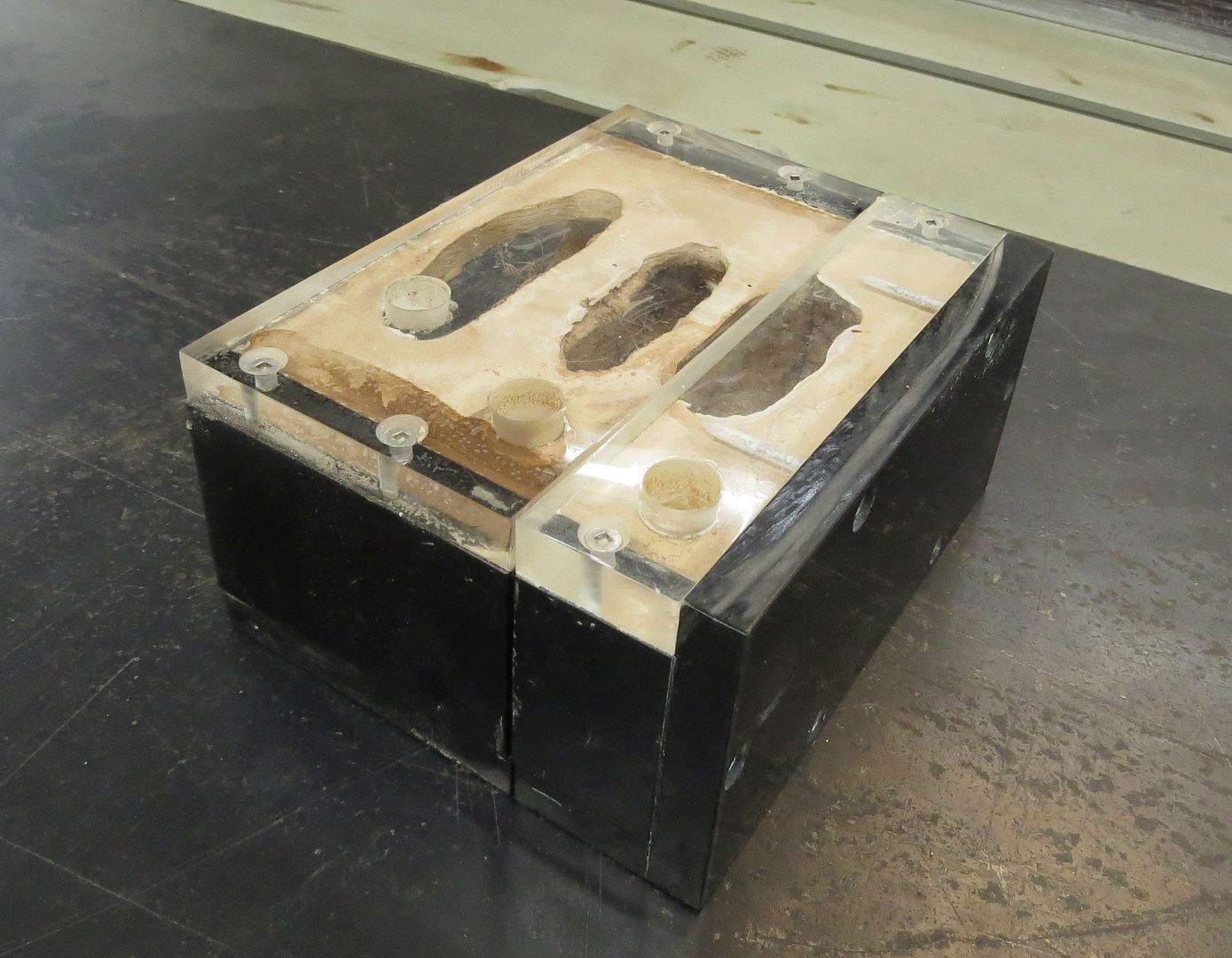

Here are two nest setups placed side to side. Each one is its own chamber to help with a movie trick. Also note the openings in the hydrostone/plaster against the plexiglass along the top.

Though empty now, ants can be added as needed. Because the front setup has windows on both sides, you can look all the way through into the second setup. Should a scene call for a wall of honeypot ants hanging in the background, to show the colony is doing well, they just slide that setup in back. But should the scene call for the colony having to rough it, they can either remove the ants or change the background nest entirely. This is a trick I'd like to incorporate into future setup designs someday.

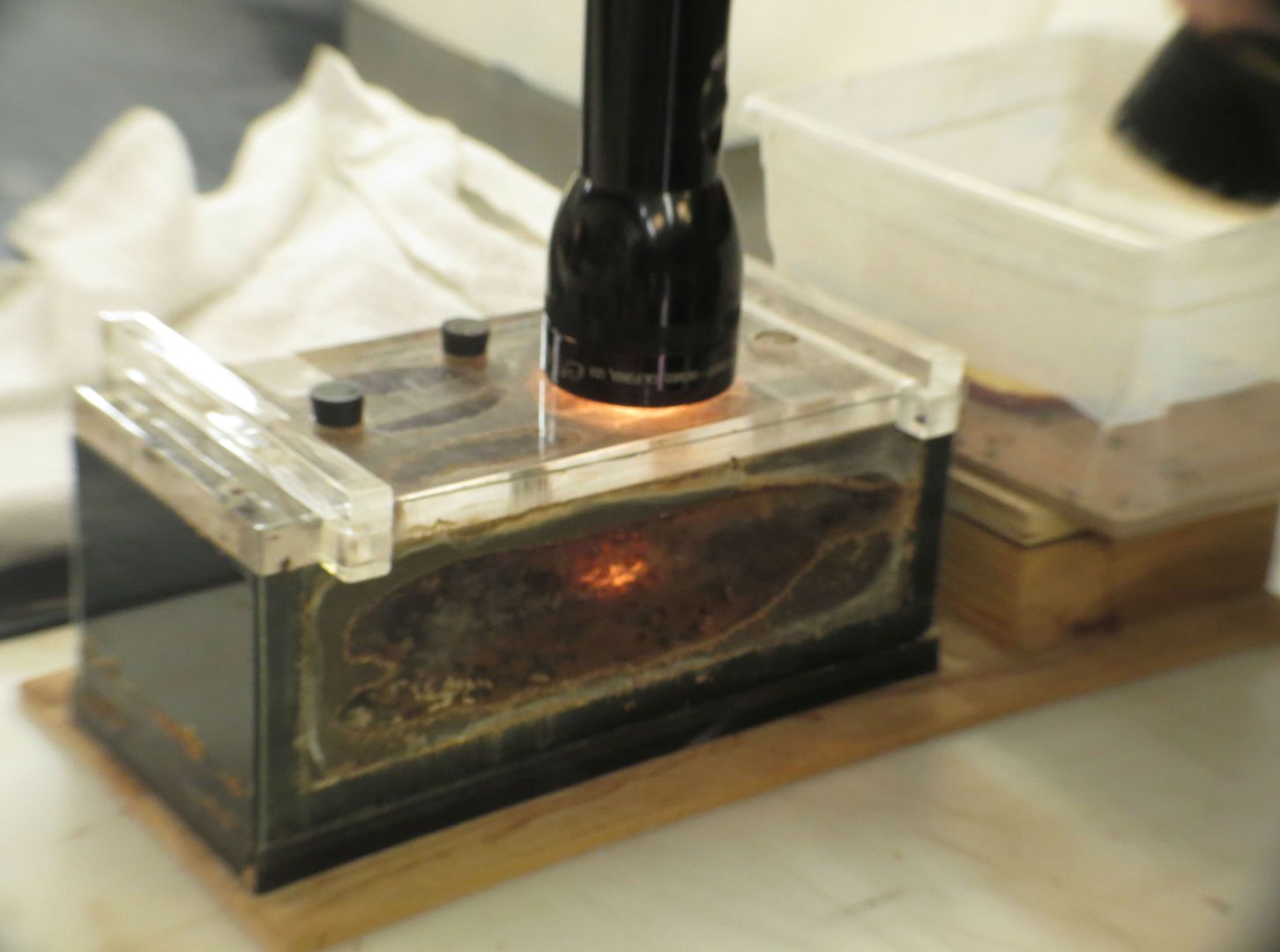

When filming honeypot ants it's always nice being able to make the honeypots glow. This is achieved by shining a flash light down through the openings in the hydrostone/plaster.

As seen here.

And here.

Condensation can be an issue at times. Ray uses a fan, on low, to blow through a tube, sending a light breeze through the nest. It's important to leave a gap between the fan and the tube, otherwise it will create a wind tunnel and can blow the ants right out of the setup or dry it out too quickly. Typically ants don't go through tunnels that have wind blowing through them, but the use of metal mesh might be required.

Watering is done by placing a tube through the bottom of the setup when casting.

Once it's dry the tube can be removed and the ends replaced by nozzles. This way water can be added beneath the ants nesting area and allowed to absorb into the rest of the setup.

Setups for his personal colonies are surprisingly simple and yet ingenious.

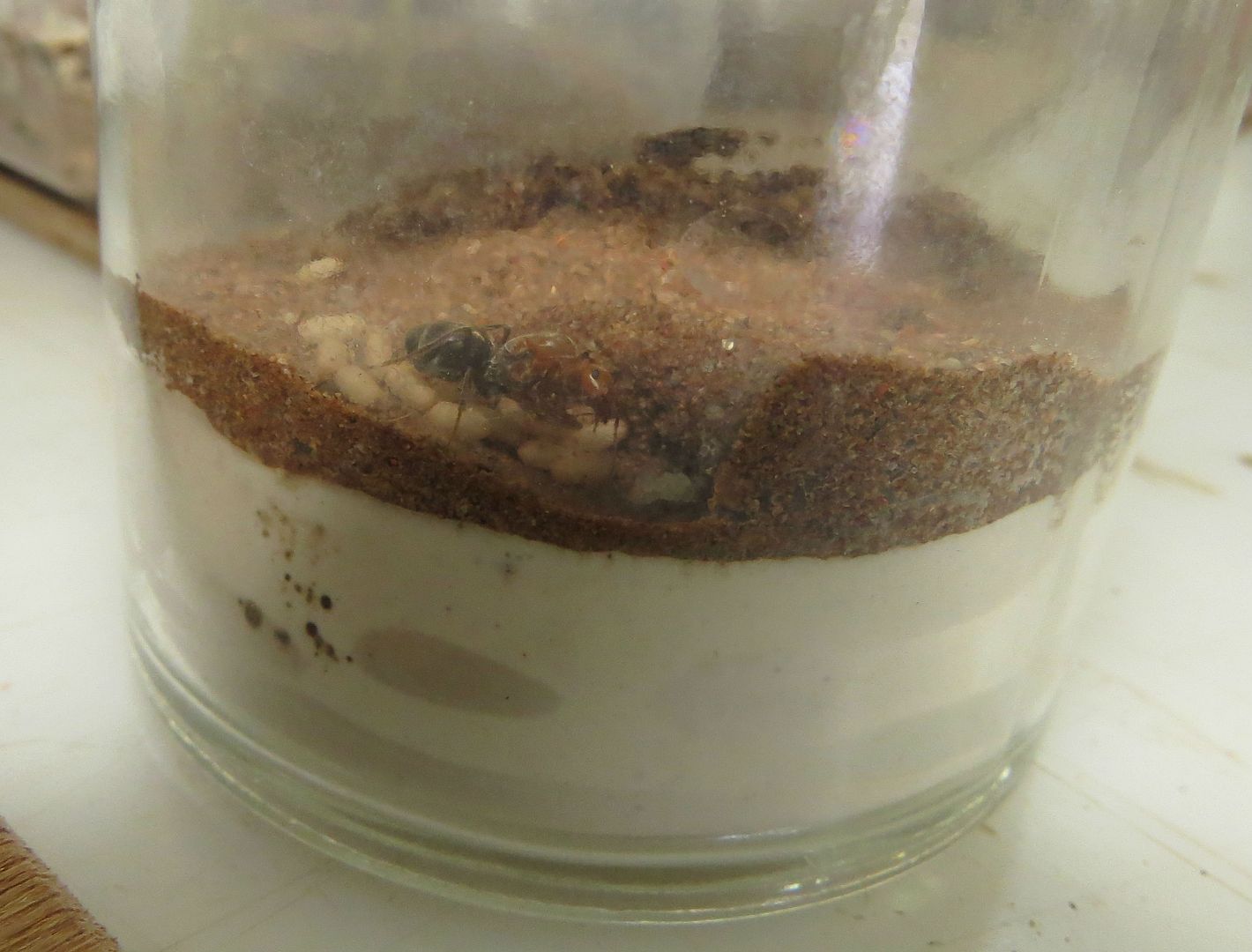

New queens are started in clusteral setups. Plaster lining the bottoms of vented containers. And a VERY THIN LAYER of soil media is added. I emphasis very little because Ray doesn't want the queen digging down into it, or building walls that will only collapse when watered. Also it was nice knowing that even he suffered from the problem "Collect 50 queens and maybe 10 of them are successful."

Queens that rear their first workers are moved into slightly larger setups. In this case a Myrmecocystus species, Honeypot ants.

Upon getting their first few repletes, he upgrades their nesting accommodation as needed.

We all got to eat a replete too. There's a trick to it because they're in a subfamily known for Formic Acid. You rupture them first to let the volatile chemicals disperse a sec, and then eat the mess left in your hand. Eating them whole also works but there's an immediate displeasing taste from the formic acid.

All his repletes had a taste of apples because he always keeps a slice of apple in the foraging area. The ants nibble at the apple over time, and then place their waste upon it, making clean up nice and easy. All you need to do is replace the apple slice.

Colonies of Pogonomyrmex, harvester ants, are notorious for stuffing crud and frass right up against the glass. To get around this, he places them in horizontal setups so the ants can be viewed from above.

He does this with Aphaenogaster too but but I'm not sure if there was any specific reason for it.

He has a colony of Atta, Leaf-cutter Ants!

Leaf-cutter Ants cut up leaves to bring home and feed to their fungus gardens.

Here you can see the media workers placing little bits of leaves among the fungi.

Near the top of the main garden lies the queen. Atta queens are the largest ants in the United States at ~25mm long. The next closest comparison are some of our Carpenter ant queens that can be as large as ~20mm long.

The only real tip he had about keeping fungus ants was to never let them grow their fungus on the ground. New queens just starting out sort of have to make do, but established colonies, even ones with basketball sized fungus gardens don't let their fungus sit on the ground. Often the fungus will grow amongst the roots of plants or on top of stones.

I learned an awful lot from Ray and can't wait to put this knowledge to good use. I'm thrilled to have met him and even asked for his autograph.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)