Wednesday, August 31, 2011

Ant Chat Episode 34 Prenolepis imparis Expirament

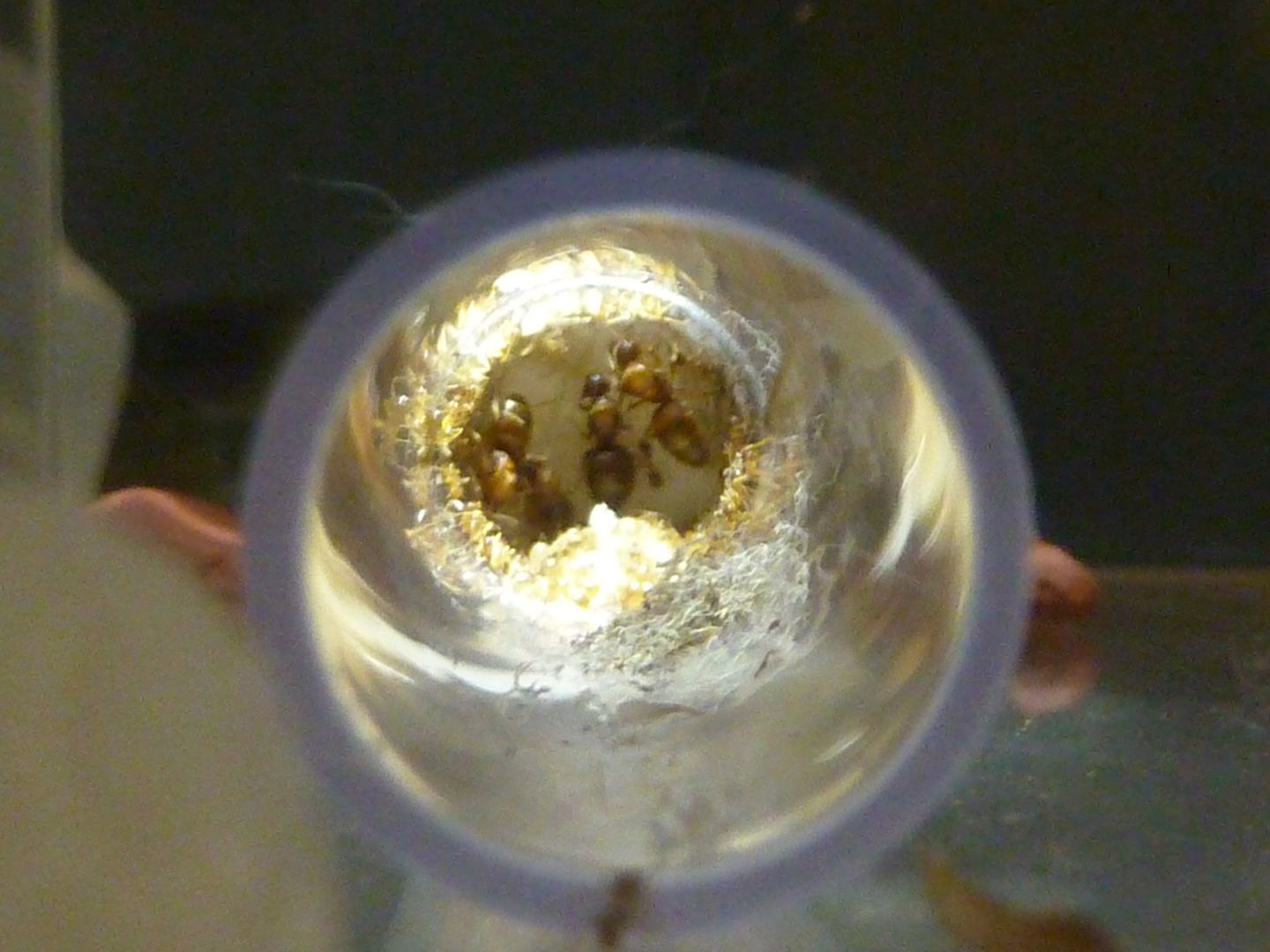

Here I took 4 young colonies of Prenolepis imparis, Winter Ants, and allowed them to share the same foraging area. I've had success in the past getting colonies to combine this way and wanted to try it again. Colonies were almost forced to step over a rolled up napkin soaked in 1:1 sugar water. Upon meeting only minor aggression was shown towards the other before they started sharing food. Colonies started exploring one another and began moving into one nest.

They're a little to far into the tube for my camera to take great photos of. Though I'm sure if I tried really hard I could come up with something.

Saturday, August 27, 2011

Bustling Milkweed

We're entering the home stretch as far as milkweeds are concerned, Asclepias species. Plants are slowly being overrun by populations of oleander aphids. By the end of September they'll be glowing orange with so many of these that leaves will grow limp and be unable to support themselves.

Outskirt populations of these aphids are being guarded by ants. This is actually kind of odd as milkweeds are supposed to be covered in hairs that release their milky sap when disturbed. Most ants can't walk over the plants without becoming stuck, though I've never seen this in action. The sap's reaction to the air is turning into a tar-like substance.

Tapinoma sessile, The Odorous House Ant, has no trouble getting past the sap defense and I regularly see them stealing nectar from milkweed flowers. Crematogaster cerasi and Camponotus chromaiodes are two new species this year I'm seeing on milkweeds. Perhaps different milkweed species have better defenses against different species of ants?

Seedpods are slowly drying up to release their seeds. The flow of sap isn't as strong here so it's safer to eat.

Eventually they grow large enough that the sap isn't an issue, but they'll still cut the main vane that's filling the leaf with sap. (I should mention this caterpillar is eating Purple Milkweed, Asclepias purpurascens, which has thicker leaves. Caterpillars otherwise eat the rim of the leaf too rather than just making a hole.)

As they get older, they become more mobile. Right down to the point where they abandon the plant to turn into a chrysalis somewhere. This way they remove themselves from the tug of war happening on the plants. I know people who've had patches of milkweed and believe that none of the monarch caterpillars they've had on their plants have ever reached adulthood because of this behavior. True enough they are a little illusive.

When they're in their last instar, they're typically nibbling the tops off the milkweed, cutting off the flow of sap to multiple leaves all at once. This is the perfect time to move them to a screened cage (in a secure, sheltered spot outside if you have air conditioning doors). From here simply feed them milkweed cuttings that are free of monarch caterpillars, or eggs, or other things unwanted. They should form a chrysalis within a week, and from there hatch as an adult in the next 10 to 14 days. Usually hatching in the morning before 12noon.

As for the milkweed plants go, I believe young ones are at risk of being eaten to heavily to come back next year. Older ones should rebound better to such attacks. Generally when planting milkweed in the garden it's a good idea to include some sort of autumn companion plant to steal the show away from the milkweed, which can often be left bare of any leaves.

Outskirt populations of these aphids are being guarded by ants. This is actually kind of odd as milkweeds are supposed to be covered in hairs that release their milky sap when disturbed. Most ants can't walk over the plants without becoming stuck, though I've never seen this in action. The sap's reaction to the air is turning into a tar-like substance.

Tapinoma sessile, The Odorous House Ant, has no trouble getting past the sap defense and I regularly see them stealing nectar from milkweed flowers. Crematogaster cerasi and Camponotus chromaiodes are two new species this year I'm seeing on milkweeds. Perhaps different milkweed species have better defenses against different species of ants?

All of this is an arms race for the monarch butterfly. Early instars have the classic warning colors, but I don't believe they're poisonous yet. Spiders and wasps make short work of them. As mentioned before milkweed sap turns to tar when exposed to air. Roughly one third of all monarch caterpillars don't survive their first day due to their mouths being fused shut. On the flip side, caterpillars need to eat the plant to gain it's toxicity. That can't happen if the aphids have drained the plants dry. Pictured above is a caterpillar who's taking advantage of the system.

Eventually they grow large enough that the sap isn't an issue, but they'll still cut the main vane that's filling the leaf with sap. (I should mention this caterpillar is eating Purple Milkweed, Asclepias purpurascens, which has thicker leaves. Caterpillars otherwise eat the rim of the leaf too rather than just making a hole.)

As they get older, they become more mobile. Right down to the point where they abandon the plant to turn into a chrysalis somewhere. This way they remove themselves from the tug of war happening on the plants. I know people who've had patches of milkweed and believe that none of the monarch caterpillars they've had on their plants have ever reached adulthood because of this behavior. True enough they are a little illusive.

When they're in their last instar, they're typically nibbling the tops off the milkweed, cutting off the flow of sap to multiple leaves all at once. This is the perfect time to move them to a screened cage (in a secure, sheltered spot outside if you have air conditioning doors). From here simply feed them milkweed cuttings that are free of monarch caterpillars, or eggs, or other things unwanted. They should form a chrysalis within a week, and from there hatch as an adult in the next 10 to 14 days. Usually hatching in the morning before 12noon.

As for the milkweed plants go, I believe young ones are at risk of being eaten to heavily to come back next year. Older ones should rebound better to such attacks. Generally when planting milkweed in the garden it's a good idea to include some sort of autumn companion plant to steal the show away from the milkweed, which can often be left bare of any leaves.

Labels:

Ants,

Aphids,

Caterpillar,

milkweed,

Monarch

Wednesday, August 24, 2011

A Friend Starts Blogging

Hay everyone, I just wanted to mention my friend in Indiana has started a blog. It's called Bumble Bees and Ants of Indiana. Naturally I was the first person to comment "First," of course. I've know him since he was a teenager, and I think it's correct to say I mentored him through ant keeping, and to an extent native plant gardens as well. As he's in the middle of prairie country it was only a matter of time before he surpassed me in some respects. He has access to a lot more remnant prairies than I do here in NJ (where we have old meadows and wetlands at best). He's even branched off and this past year started several bumblebee hives. Next year if all goes well I believe he's starting with honeybees. So hopefully he really takes to blogging and we get some nice posts over there.

Labels:

Ants,

Bees,

Bumblebees

Saturday, August 20, 2011

Butterflies at Mt. Cube.

|

| A chrysalis to the Pipevine Swallowtail. |

I had another exciting class at the Mt. Cuba Center today. This time the class was on Butterflies in Your Garden, which focused on the most common and showiest Lepidoptera you can see flying in the daylight hours. The lecture was well constructed but had a few omissions like Hummingbird Moths, Mourning Cloak, and Skippers as a whole. They were brought up and talked about as we chanced upon them during the tour though so that's fine. It's hard planning around nature.

The tour started with a bang as we went to the Round Garden. It's a circular pavilion with a rather nice pool in the middle

From there we moved to a little spot next to their Trial Garden. It doesn't actually have a name but it's a nice garden bed. A massive Great Spangled Fritillary, Speyeria cybele, immediately caught my eye. And best of all it was very cooperative for my camera.

These are about the same size as the Monarch butterfly, if not slightly bigger. They use native violets as a host plant, however, females only lay eggs in the autumn and not necessarily anywhere near a violet. The poor caterpillars hatch and over winter with nothing to eat for 5 to 8 months. Barely any of them survive.

So to sustain a population of these it sounds like lots of violets spread around the garden are needed. I read in Caterpillars of Eastern North America: A Guide to Identification and Natural History (Princeton Field Guides)

The meadow garden had slightly less flying through but I've seen from past visits it can be swarming with butterflies, especially Monarchs. Here we see Virginia Ctenucha, Ctenucha virginica, which wasn't mentioned on the tour. I feel like it's trying to mimic some kind of roach but I've no idea why. This was just something I noticed.

Red-Spotted Purple, Limenitis arthemis. Here's one that was mentioned and I've seen them flying around my garden too. It's hard to tell from the photo but the upper corners of the wings have red spots on them, well more like orange blushing. This is a species that you'll find on rotting fruit, dung, and sipping at tree sap.

Also in their meadow garden was this caterpillar (sawfly larva?) which was on Joe Pye Weed but I've never known that genus to yield many caterpillars to anything interesting. At least nothing that feeds on it during the day.

Here is an inch worm of some sort. I had them identified at one point but I forgot what it's called. Basically they feed on composite flowers and take on the color of the bloom they're nibbling on, in this case Ironweed.

So that was my visit. :)

Labels:

Book,

Butterflies,

Caterpillar,

Color,

Lepidoptera,

Moths,

Wildflowers

Thursday, August 18, 2011

Solomon's Seal

Solomon's Seal, Polygonatum commutatum, I think. It's the most common one I think though there are other Polygonatum species around. This was another woodland highlight they had growing at the Mt. Cuba Center. It's well past flowering but unlike other spring ephemerals it stick around longer in the year. I feel like the majority spring ephemerals are pollinated by either flies or beetles, but this is one that's actually geared towards bees.

The fruit are these charming blue cherry-like berries which are eaten mostly by woodland birds

The fruit are these charming blue cherry-like berries which are eaten mostly by woodland birds

Labels:

Fruit,

Spring,

Wildflowers

Wednesday, August 17, 2011

My Monarch Meadow

Proof, that the Hummingbirds have been visiting my yard all year and aren't just in my head! They've even featured in a short video I made, towards the end.

We open with a variety of carpenter ant tending some aphids. Camponotus chromaiodes is similar to C. pennsylvanicus but has red on 2/3rds of the mesosoma. I have never seen ants tending the aphids on milkweed before. Normally the aphids seem to overrun the plant, eventually causing the stem to turn a brilliant yellow orange from the sheer number. So I thought this was neat to find. Part of the reason might be this is a young colony in my yard that's only recently grown to about 50 workers this past year.

While naming the video I came up with the phrase Monarch Meadow. And I thought wow, that is so catchy that it has to be a real place. Surely some nature preserve somewhere has coined it already. So I googled it and sure enough there is a place named that!

And it's the most boring place on earth. This is The Best example of a place with the wrong name. Perhaps you've driven past an Oak Drive and noticed the lack of oak, or a Poplar terrace that doesn't have any tulip or poplar trees. There's a place near me called The Meadows who's mostly paved apartment complex. What do Monarchs have to do with this place? Sure they could mean it in a sovereignty sense but even then sharing an apartment complex, each with it's own Washer and Dryer (gasp), doesn't exactly scream royalty.

A google image search doesn't yield much better results. In fact you don't need to scroll that far down the results before coming across one of my images.

I'm surprised Prairie Moon Nursery, or Prairie Nursery haven't marketed some kind of garden package with preselected Monarch plants.

We open with a variety of carpenter ant tending some aphids. Camponotus chromaiodes is similar to C. pennsylvanicus but has red on 2/3rds of the mesosoma. I have never seen ants tending the aphids on milkweed before. Normally the aphids seem to overrun the plant, eventually causing the stem to turn a brilliant yellow orange from the sheer number. So I thought this was neat to find. Part of the reason might be this is a young colony in my yard that's only recently grown to about 50 workers this past year.

While naming the video I came up with the phrase Monarch Meadow. And I thought wow, that is so catchy that it has to be a real place. Surely some nature preserve somewhere has coined it already. So I googled it and sure enough there is a place named that!

And it's the most boring place on earth. This is The Best example of a place with the wrong name. Perhaps you've driven past an Oak Drive and noticed the lack of oak, or a Poplar terrace that doesn't have any tulip or poplar trees. There's a place near me called The Meadows who's mostly paved apartment complex. What do Monarchs have to do with this place? Sure they could mean it in a sovereignty sense but even then sharing an apartment complex, each with it's own Washer and Dryer (gasp), doesn't exactly scream royalty.

A google image search doesn't yield much better results. In fact you don't need to scroll that far down the results before coming across one of my images.

I'm surprised Prairie Moon Nursery, or Prairie Nursery haven't marketed some kind of garden package with preselected Monarch plants.

Labels:

Hummingbirds,

Meadow,

Monarch,

Video

Monday, August 15, 2011

The Meadow at Mt. Cuba

I attended another Meadow Studies class at the Mt. Cuba Center this month. The previous one from last month I found to be a little boring. Their their meadow is primarily grasses, and rather few plants were blooming at the time. To their credit I am bias against grasses, and generally anything wind pollinated. Lush grassy meadows have their place, but during the month of July they look like a lawn in desperate need of mowing. As the year progresses though species like Big Bluestem, Andropogon gerardii, and Yellow Indian Grass, Sorghastrum nutans, come into their own. These tall grasses grow to be 6' high and there's nothing more majestic looking that watching their seed heads flowing with the wind. The whole meadow comes alive swaying with every gust like an ocean of plants. Unfortunately the effect doesn't photograph well, at least not with my camera, and the perspective seems to always be off somehow.

Even here peering through a mossy clearing the grasses barely look 3' tall. As the grasses grow taller they become easier to appreciate.

Before going to the meadow they had patches of Spotted Touch-me-not, Impatiens capensis, flowering. This native Impatient is anything but. Seeds germinate after 2 winters and the resulting plant is an annual. They're fun plants because of their exploding seed pods, but if you're looking for any sort of predictability as to where they'll come up, you need to plant seeds in the same spot 3 years in a row. From there they're a delightful weed, growing in wet spots, and attracting hummingbirds. (Supposedly the sap helps clear up poison ivy but I'm not advocating holistic remedies. I would be willing to try it out though.)

Bottle Gentian, Gentiana andrewsii, was also in bloom. These flowers are fussy and hard for most bees to open. The idea with the tight petioles is to discourage ants from stealing nectar. As you can see, carpenter bees and perhaps others, have little issue just cutting holes right through the flowers to get the nectar. This happens to a lot of tube and bell shaped flowers.

Brown-Eyed Susan, Rudbeckia triloba. This is also called Thin-leaved Coneflower, but I feel that implies a different genus. It didn't seem to be spreading around like the other Rudbeckia species in their meadow.

Monarchs were all over their milkweed. They have lots of species of milkweed there but most of it is well past flowering. Also an abundance of insects that help nibble the plants to the ground were starting to show up.

Here is a some type of cultivated Coneflower from one of their other gardens. The tube shaped flowers almost imply hummingbirds should drink from them.

There were many other things flowering in their meadow, it's just I'm not into things like Obedient plant, Physostegia virginiana, and some type of perennial sunflower, Helianthus microcephalus. There were some early Goldenrods too.

Even here peering through a mossy clearing the grasses barely look 3' tall. As the grasses grow taller they become easier to appreciate.

Before going to the meadow they had patches of Spotted Touch-me-not, Impatiens capensis, flowering. This native Impatient is anything but. Seeds germinate after 2 winters and the resulting plant is an annual. They're fun plants because of their exploding seed pods, but if you're looking for any sort of predictability as to where they'll come up, you need to plant seeds in the same spot 3 years in a row. From there they're a delightful weed, growing in wet spots, and attracting hummingbirds. (Supposedly the sap helps clear up poison ivy but I'm not advocating holistic remedies. I would be willing to try it out though.)

Bottle Gentian, Gentiana andrewsii, was also in bloom. These flowers are fussy and hard for most bees to open. The idea with the tight petioles is to discourage ants from stealing nectar. As you can see, carpenter bees and perhaps others, have little issue just cutting holes right through the flowers to get the nectar. This happens to a lot of tube and bell shaped flowers.

Moving out into the meadow, the real highlights were the Wild Senna, Cassia hebecarpa, and assorted Joe Pye Weeds, Eutrochium fistulosum and Eutrochorium maculatum.

Note: Joe Pye Weed was formerly in the genus Eupatorium. That genus still exists but I believe it consists mostly of the taller white flowering species that aren't Boneset. Eutrochium includes all purple/pink flowering members of Eupatorium now. Personally I think this is a conspiracy concocted by the plant labeling community.

Anyway, I feel like they understated their Wild Senna a bit. It was in full bloom and not really mentioned until I asked. They did this with a number of plants but it's not like it was a bad tour. Actually we got up close and personal with 25 meadow species with lots of other goodies along the way. The instructor was more than happy to talk about all plants in the gardens people asked about.

This is the host plant to the Cloudless Sulphur, Phoebis sennae, which isn't the most common butterfly around, but it's certainly unique enough looking to warrant their host plant in any butterfly garden. The pea-like seeds are also an excellent food source for certain birds.

Brown-Eyed Susan, Rudbeckia triloba. This is also called Thin-leaved Coneflower, but I feel that implies a different genus. It didn't seem to be spreading around like the other Rudbeckia species in their meadow.

Monarchs were all over their milkweed. They have lots of species of milkweed there but most of it is well past flowering. Also an abundance of insects that help nibble the plants to the ground were starting to show up.

I found this skipper on their Ironweed, Vernonia noveboracensis, to be rather attractive. The colors reminded me of a robin or some sort of bird.

There were many other things flowering in their meadow, it's just I'm not into things like Obedient plant, Physostegia virginiana, and some type of perennial sunflower, Helianthus microcephalus. There were some early Goldenrods too.

Saturday, August 13, 2011

Mad Plant Catalog?

Someone thought this mildly offensive image would make a great cover to the Plant Delights Nursery 2011 catalog.

Labels:

Plants

Wednesday, August 10, 2011

What Grows Around a Community Garden

Well established community gardens are amazing, especially ones that have been around for years. As each new crop of gardeners go to plant their goods what happens is they typically find seeds and perennial crops from the person before. Unwanted plants seem to have been transplanted to the outskirts along the garden. And over the years a couple of species in particular seem to have flourished here.

There are hedges of cup plant, prairie coneflower, what I'm guessing is fennel in flower, a yellow flowering yarrow, and they had the most amazing sunflowers I've ever seen. It's like someone loved the color yellow and planted everything they could get to grow 5' or taller.

Most of this is one sunflower! The one stem was about 6" thick and had branches coming out of each node, where the leaves are formed. There were leaves on the lower ones at one point but they slowly die off over the year. So this massive sunflower had branches of other sunflowers coming out of it. It's amazing to think earlier in the year this was just a 1cm seed.

There weren't as many bees flying around as you might think. There were lots of bumblebees around but nothing I hadn't seen before.

There were a bunch of goldfinches flying around too but they were doing their best to dodge me at every turn.

I'm actually not doing this place justice because they were growing lots of other goodies, like Corn and just about everything else someone can grow.

There are hedges of cup plant, prairie coneflower, what I'm guessing is fennel in flower, a yellow flowering yarrow, and they had the most amazing sunflowers I've ever seen. It's like someone loved the color yellow and planted everything they could get to grow 5' or taller.

Most of this is one sunflower! The one stem was about 6" thick and had branches coming out of each node, where the leaves are formed. There were leaves on the lower ones at one point but they slowly die off over the year. So this massive sunflower had branches of other sunflowers coming out of it. It's amazing to think earlier in the year this was just a 1cm seed.

There weren't as many bees flying around as you might think. There were lots of bumblebees around but nothing I hadn't seen before.

There were a bunch of goldfinches flying around too but they were doing their best to dodge me at every turn.

I'm actually not doing this place justice because they were growing lots of other goodies, like Corn and just about everything else someone can grow.

Tuesday, August 9, 2011

More Butterflies of Summer

There is something like 250+ species of Skipper in North America. These are all rather small butterflies that get their name for their sort of hopping habit. Lots of species hang out in groups and all fly together making the garden bustling with activity. They're often ignored though for their assorted brown and orange color scheme. Caterpillars only feed at night and are almost never seen either. Most species use native grasses as host plants but a few dabble in Oak and Legumes as well. This rather dark species above I've only started noticing this year. I'm hoping it's the Wild Indigo Duskywing, Erynnis baptisiae, which uses Blue False Indigo, Baptisia australis, as a host plant.

Here's a better picture of what might be the same species. (I'm also glad they found a use for the ironweed.)

Other skippers have started showing up as well. This one is smaller and more of the standard when I think of skippers. It's slightly unusual in how pale beige it is, as most species seem to be dark brown. The only species I can really identify at a glance is the Silver-Spotted Skipper, Epargyreum clarus. It's larger than most skippers, brown, and with a bold white and orange stripe crossing it's wings.

Here on the Joe Pye Weed is the black form of the Eastern Tiger Swallowtail, Papilio glaucus, and a rather beat up one at that. The light reflecting under the wings is creating a slight yellow appearance.

A new species I've started seeing is the Spicebush Swallowtail, Papilio troilus. The wings are always lined with white or yellow spots, but there's also this large area of either blue, green, or teal to the rear of the wings. I took this picture at a nursery which sells an unidentified species of Spicebush. I never buy plants when they're not identified to species level. However, in this case identifying to genus level is all that's needed. As it turns out there are only 3 species of Spicebush in the US and all of them are native. I'm probably going to go back and buy a shrub.

Saturday, August 6, 2011

1 Queen, 2 Queen, 3 Queen, 4

Colonies of Tapinoma sessile, Odorous House Ant, normally stay outside. They thrive in places where there's lots of grass, and debris laying around. I've also found then nesting in hollow cavities in logs, and mason bee tubes. They're opportunistic and will nest anywhere they can. The common name comes from their habit of nesting in homes. The odor only occurs from crushing them so it might be better to discourage them than to fight back. They don't do a whole lot of nest building so sealing up where they're coming in from is an easy option if applicable. The smell is nothing unbearable I'm told.

Shortly after their mating season, April to June, (occasionally July), queen number for each colony jumps drastically. Presumably they are either inbreeding within the nest, or colonies generally accept queens they come across into the nest.

This leads to a lot more queens suddenly appearing into the nest and fuels budding behavior. At some point in the year colonies will divide as needed to setup new nesting sites elsewhere. Once divided colonies typically don't want anything to do with one another. The more urban the location though, it seems the more connected these colonies remain and they end up getting much larger than they would out in a suburban or rural area. There's something about city life that encourages colonies to stay connected in a series of sub-colonies as opposed to setting up new ones. What's neat though is that individual queens are fully capable of starting a colony on their own.

This kind of variation within a single species I've learned is more common in ants than previously thought. I've seen this in Monomorium minimum, both queen inbreeding, and loan queen colony founding. The Red Imported Fire Ant, Solenopsis invicta, do this too. With fire ants it's more genetically divided. Monogynic (one queen) colonies produce monogynic colony founding queens while polygynic (more than one queen) reproduce by queen adoption and budding. What's really neat about fire ants is their reaction to water. When floods come, all the members of the colony form a living raft and float away, but while adrift there's nothing stopping two colonies from bumping into one another. Floating for survival is no time for war, so the two colonies may merge into one floating raft, and upon reaching land they remain as one colony regardless of mono or polygynic status before the flood. Perhaps this is how polygynic colonies got their start with this species.

I've seen colonies of Temnothorax sometimes combine to better survive the winter. The following spring they disperse and go their separate ways, though it's unclear if the workers are pared with their genetic mother or just going with the flow. Camponotus pennsylvanicus colonies are strictly monogynic but they still produce sub-colonies as extensions of their nest and territory. Each autumn these satellite locations are abandoned to better overwinter in one location.

Perhaps the most notorious ant to talk about queen number is the Argentine Ant, Linepithema humile. In North America at least, this species spreads exclusively by budding. Queens mate inside the nest causing their numbers to skyrocket at one time of the year. Workers in L. humile have very high standards when it comes to queens though and each year they kill off ~90% of their own queens. This massacre occurs at the same time of year each year. It would seem they don't like their queens to be more than a year old, perhaps to maintain queens at the peak of their egg laying capacity.

Though the queens to polygynic colonies ultimately produce larger colonies, their monogynic counterparts typically live longer.

Shortly after their mating season, April to June, (occasionally July), queen number for each colony jumps drastically. Presumably they are either inbreeding within the nest, or colonies generally accept queens they come across into the nest.

This leads to a lot more queens suddenly appearing into the nest and fuels budding behavior. At some point in the year colonies will divide as needed to setup new nesting sites elsewhere. Once divided colonies typically don't want anything to do with one another. The more urban the location though, it seems the more connected these colonies remain and they end up getting much larger than they would out in a suburban or rural area. There's something about city life that encourages colonies to stay connected in a series of sub-colonies as opposed to setting up new ones. What's neat though is that individual queens are fully capable of starting a colony on their own.

This kind of variation within a single species I've learned is more common in ants than previously thought. I've seen this in Monomorium minimum, both queen inbreeding, and loan queen colony founding. The Red Imported Fire Ant, Solenopsis invicta, do this too. With fire ants it's more genetically divided. Monogynic (one queen) colonies produce monogynic colony founding queens while polygynic (more than one queen) reproduce by queen adoption and budding. What's really neat about fire ants is their reaction to water. When floods come, all the members of the colony form a living raft and float away, but while adrift there's nothing stopping two colonies from bumping into one another. Floating for survival is no time for war, so the two colonies may merge into one floating raft, and upon reaching land they remain as one colony regardless of mono or polygynic status before the flood. Perhaps this is how polygynic colonies got their start with this species.

I've seen colonies of Temnothorax sometimes combine to better survive the winter. The following spring they disperse and go their separate ways, though it's unclear if the workers are pared with their genetic mother or just going with the flow. Camponotus pennsylvanicus colonies are strictly monogynic but they still produce sub-colonies as extensions of their nest and territory. Each autumn these satellite locations are abandoned to better overwinter in one location.

Perhaps the most notorious ant to talk about queen number is the Argentine Ant, Linepithema humile. In North America at least, this species spreads exclusively by budding. Queens mate inside the nest causing their numbers to skyrocket at one time of the year. Workers in L. humile have very high standards when it comes to queens though and each year they kill off ~90% of their own queens. This massacre occurs at the same time of year each year. It would seem they don't like their queens to be more than a year old, perhaps to maintain queens at the peak of their egg laying capacity.

Though the queens to polygynic colonies ultimately produce larger colonies, their monogynic counterparts typically live longer.

Labels:

Ants,

Myrmecology,

Queen,

sessile,

Tapinoma

Wednesday, August 3, 2011

Ant Chat Episode 33: Myrmecochory

I've already done a short show about Myrmecochory which you can see by clicking here. It was such a popular show, at least on youtube, that I decided to do another one but this time with different ants. I will hopefully do this as an annual event each year but I hope to mix it up with other plants that have elaiosome on their seeds. Unfortunately Trilliums are the only plants that I seem to have any success with as far as seed distribution goes. The Hepatica I grew this year for whatever reason didn't get any ant attention.

Fun Fact: To my knowledge there wasn't a word for seed dispersal by wasps before this episode was made. I asked James C. Trager what that might be called and he suggested the word Sphecochory. Now I'm not sure if planting in tales the seed being successfully making it to a spot where it can grow. Yellow Jackets do nest underground but I've also seen paper wasps raiding the pods for seeds and the flesh within too. Successful planting probably happens rarely but the seed is still at least being taken away from the parent plant and making it into the ground. So maybe Sphecochory will make it's way into the dictionary someday.

|

| A Trillium seed pod turned inside out. |

|

| An Aphaenogaster rudis walking through the Trillium seeds. |

|

| Nylanderia flavipes stealing the elaiosome from Trillium seeds. |

|

| An unexpected thief terrorizes the ants away, and begins chewing off one of the seeds. |

|

| Sphecochory - Seed distribution by wasps. Why not. |

|

| A Camponotus castaneus locating a Trillium seed. |

|

| A Camponotus castaneus hauling a Trillium seed home. |

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)