The earliest of the violets have started blooming. I'm not certain what species this is though. If you have them in your lawn I suggest transplanting some into your garden. If they're already in your garden, don't worry if they reproduce into your lawn.

These are the host plant to a number of Lepidoptera. The issue though is the caterpillars eat the leaves when the plants are above the 4 inch mark or the average mowed lawn. With the plants in the garden though they avoid being mowed and thus the caterpillar becomes a butterfly. The Varigated Fritillary is one such butterfly with wide distribution, that uses violets. I can't say that I've ever seen it though, and it does use other host plants like may apple and passionflower.

Also note in the picture above all the little 2 leaf violets coming up. Unlike pansies, violets come back every year and usually do good at reproducing. Assuming the right ant species is present too you may see violets popping up far away too. Some violets, but I don't think all, entice ants to plant their seeds for them. This helps the violets spread so hundreds of violets don't end up growing in a small space. It means free plants either way.

While I've never seen pollination happen I know it does occur from all the seedlings. I read that small bees like mason bees are the ideal pollinator of this plant. Moths and Butterflies might also.

Very pretty plant. I think I have 3 other types elsewhere too.

Wednesday, March 31, 2010

Tuesday, March 30, 2010

Identification and Distribution of Lasius in North America

Sorry for no updates in the past couple of days. Been a little busy with work, podcasting, and researching ants. I'm posting this here as a backup.

Scape - Long antenna segment that touches the connects with the head.

Lasius Niger Group

Lasius neoniger SW, SC, SE, NW, NC, NE

This is the most common niger species found in the US. Found in fields nesting in open soil or under stones. Can hybridize with Lasius alienus. Workers tend to be brown in color with dark legs that are evenly colored. Scape and Tibiae are furry. Queens tend to have a velvet like sheen to the abdomen when viewed at certain angles, but this is also found in other Lasius.

Lasius alienus SW, SC, SE, NW, NC, NE

The most common niger species found in wooded areas. Found in forests, nesting in soil, rotten logs, and stumps. Can hybridize with Lasius neoniger. Workers tend to be black with lighter legs, usually yellow in color. Scape is lacking hair. Seta Count is less than 40, usually less than 20 standing hairs. Queens seta count is never more than 10 and is usually 0.

Lasius niger SW, NW, and Eastern Canada

It's unknown how the SW, and NW populations arrived, or did they originated there and spread to Europe and Asia where they're more common? Who knows. The Eastern Canada population only recently arrived from Europe within the last 50 years. (I know this by memory and am still looking for the source.)

Lasius alienus, and L. neoniger are subspecies of Lasius niger. It is found in both forests and fields, they nest understones and in open soil. Workers tend to be black like L. alienus. Scape and Tibiae are furry like L. neoniger. Legs tend to be dark but yellow at joints, however I don't know how consistent this is. Queens are described as being similar to L. alineus but are covered in hair like L. neoniger. (One wonders if the SW, and NW population isn't just a hybrid between L. neoniger and L. alienus in need of it's own species name.)

Lasius crypticus SW, NW, NC

Found in fields mostly but sometimes woodland. Nest under stones. Similar to Lasius neoniger but darker in color. Scape and Tibiae are mostly free of hair.

Lasius pallitarsis SW, NW, NC, Alaska, Most of Canada.

Found in forests and fields, nesting under stones. Amber Brown in color out west but to similar to L. umbratus in the east to rely on color alone. Has an extra tooth on the mandibles if you have a microscope. Scape tends to be free of hair. Legs tend to be lighter in color. Supposedly this species produces an odor but that hasn't been confirmed. What's really odd is the source mentioned the odor and also talked about umbratus species using them as a host. Niger group species aren't known to produce an odor and one would think for such a widely distributed species this would be an easy confirm or deny. They were being called by their former name though Lasius sitkaensis. (Assuming there is a population of them in Canada that produces the citronella odor unlike in the rest of it's range perhaps L. sitkanensis, or another name, should be reinstated for that group?)

Lasius sitiens SW

Found in forests and fields, usually at high elevations between 7000-8000 feet, give or take. Juniper shrubs and dry open places also describes their environment. Nest under stones. These are a subterranean forager (which is odd for the niger group but that's where they are) Eye's can be smaller and L. flavus like (also very odd for the niger group), but the maxillary palp doesn't lie. Scape and Tibiae and for that matter The Entire Body mostly lacking hair.

Lasius xerophilus SW (Only found in New Mexico)

Found nesting in sandy soil with small mounds. Similar to L. neoniger but they have more erect hair on the Tibiae.

Lasius Flavus Group

Queens are niger group-like but are a tiny bit smaller and lighter in color.

Lasius fallax SW, NW, NC

This species isn't as common as L. flavus or L. nearcticus. Found in forest clearings where they nest under stones. Scape and Tibia have hair.

Lasius flavus SW, SC, SE, NW, NC, NE

Found in forests and fields (though I want to say finding them nesting in fields is more typical of Europe where they make mounds too.) nest in soil under stones or fallen logs. Open sparsely covered ground is ideal. Scape and Tibia are reasonably free of erect hair. See paragraph below.

Lasius nearcticus SW, SC, SE, NW, NC, NE

Found in dense woodlands. Nest in moist soil under stones or fallen logs. Thick leaf litter is a must. This is a subspecies of Lasius flavus. Scape and Tibia are reasonably free of erect hair.

Lasius flavus and L. nearcticus are hard to tell apart in the western US. They hybridize with greater frequency out there. This doesn't happen as much in the eastern US. Head to head L. nearcticus tends to have a smaller eye compared to L. flavus who have similar sized heads. Lasius flavus's head also tends to narrow some at the mandibles while L. nearcticus doesn't do as much. Supposidly L. flavus workers are polymorphic and L. nearcticus are monomorphic but I find this to not be true. Perhaps it's more accurate to say L. flavus is MORE polymorphic than L. nearcticus tends to be. This theme of Lasius nearcticus having longer traits (sometimes only by fractions of a millimeter) is consistent, but still makes the two species hard to tell apart.

Lasius Umbratus Group

Queens have a smaller abdomen than Niger and Flavus group. These are social parasites of the Niger group. Some are more select than others.

Lasius umbratus SW, SC, SE, NW, NC, NE

This is the most common and wide spread species in this group. Found in both forests and fields, nests under stones in rotting logs and in rotting stumps. Scape and Tibia are not very hairy. This ant is kind of the default model for four subspecies: minutus, speculiventris, subumbratus, and vestitus. They use Lasius alienus, neoniger, and niger as host species.

Lasius minutus NC, NE

Subspecies of Lasius umbratus. Found in sphagnum bogs, dry forests, or swampy fields. Nests in soil often with mounds or masonry domes. Lots of erect hairs all over the body except for the Tibiae which is mostly free of hair.

Queens supposidly share mimetic coloration with host species Lasius alienus. (Wheeler, W.M. 1917 : 167-176)

Lasius speculiventris SC, SE, NC, NE (New Jersey)

Subspecies of Lasius umbratus. Found in forests and field. Nest under stones and in rotten wood. Abdomen is mostly free of hair. Scape and Legs have lots of erect hairs!

Queens might use Lasius minutus as a host along with other Lasius. This is interesting because L. minutus is itself a social parasite. (Kannowski, 1959b : 138-141 153-154)

Lasius subumbratus SW, NW

Subspecies of Lasius umbratus. Found in forests and fields. Nests under stones and rotting logs. Replaces Lasius umbratus where found? Supposedly Scape and Legs have dense pubescence (thin layer of fuzz) and occasionally standing hairs. Ant Web specimens don't seem to have this though, at least not on the legs. The hairs must be very short if they do.

Lasius vestitus SW, NW

Subspecies of Lasius umbratus. Found in forests. Nests in rotting logs and stumps. Replaces L. umbratus where found. Scape and Tibia have lots of hairs. Abdomen is especially covered with lots of erect hairs!

Lasius nevadensis SW (Nevada) Only found in Nevada.

Found in open forests. Nests either under stones or in exposed soil. Scape and Tibiae have longer hair than L. umbratus. Not as shiny as L. vestitus. Has more hair than L. vestitus but less than L. subumbratus.

Lasius atopus SW (Only found in California)

Nest in soil under stones. The Scape is very long for a Lasius extending well above the head. This is unique enough that that's all you need to know to ID this species.

Lasius humilis SW

Found in open woodland and moist fields. Nest under stones. Is found in what has been described as a mountain meadow. Workers are small and pale colored.

Lasius Claviger Group

Queens are very similar to Umbratus group species but most produce a citronella odor. These are also social parasites of Niger group species.

Because Claviger used to be it's own genus (Acanthomyops) the language of identifying them is a little different. The Dorsum side of the Propodeum (top of the last thorax segment), and the Gula (underside of the head, behind the palp) are the main ones. A side view of the ant is best. Some Claviger species have Barbulated or Plumose hair. Barbulated hair means the hair has lots of barbs poking all along the hair. See the top of this ant's head. Plumose hair is similar to barbulated hair but the majority of the barbs at at the tips or top third of the hair, and the effect is greater. see here.

By far the most common two species found are Lasius claviger and Lasius interjectus.

Lasius claviger SW, SC, SE, NC, NE

Found in forests and fields. Nest in soil, and rotting wood. Different from L. interjectus by having hair uniformly along the dorsum of the abdomen. Different from L. latipes by having less hair under it's Gula. Hybridization with Lasius latipes has been noted (Umphrey & Danzmann, 1998 : 431-440)

Lasius subglaber SW, SC, SE, NC, NE

Subspecies of Lasius claviger. Found in forests and fields. Nest in soil, in or under rotting logs and stumps. Mostly short or very little body hair. Gula is usually free of hair.

Lasius interjectus SW, SC, SE, NW, NC, NE

Found in forests and fields. Nest in soil, under stones, rotting logs, and in stumps. Next to walls of buildings is also noted. Propodeum is very convexed. Differs from L. claviger in that hairs on abdomen fall in rows fallowing the tergites (plates that make up the abdomen). Gula has hair.

Lasius arizonicus SW

Subspecies of Lasius interjectus. Found at high altitudes between 5000-8500 feet above sealevel. Nest understones. Easily recognized by almost completely lacking pubescence (thin layer of fuzz) and having a very shiny body. Hairs are very sparse on legs. Propodeum is very convex.

Lasius californicus SW

Subspecies of Lasius interjectus. Found under stones in mountains at mid levels. I couldn't find exact heights. Body hair is somewhat barbulated and is said to be related to L. colei. This is odd because L. colei isn't considered a subspecies of L. interjectus and yet both have the barbulated hair. Gula and Clypeus has 10 or so standing hairs each. Dorsum of gaster with fair amount of standing hairs.

Lasius coloradensis SW, NW, NC (No pictures found, sorry)

Subspecies of Lasius interjectus. Despite being a subspecies of L. interjectus, I read it's easier to confuse this with Lasius claviger. Workers have more body hair but it's shorter in length. L. claviger and L. coloradensis have divided distribution and are rarely found in the same locations.

Lasius mexicanus Mexico

Subspecies of Lasius interjectus. Found in woodlands at high elevations 7900-9000 feet above sea level. Nest under stones. Pubescence on abdomen is dilute to moderate. Hairs are long! Body is shiny. Propodeum is usually convex.

Lasius bureni NC (Wisconsin) Only Found in Wisconsin.

Long standing hairs on Gula. Shorter hairs on dorsum of abdomen. Said to be brown or "yellow-brown" in color. (If that's possible. They might be referring to the uneven color pattern on the head as seen in antweb's pictures.)

Lasius colei SW Only found in the New Mexico and Arizona area. Very uncommon.

Related to Lasius californicus. Body hair is barbulated. Gula and Clypeus have only 4 to 8 standing hairs each. Less hair on the abdomen than L. californicus.

Lasius creightoni SW (Utah) Only found in Utah.

Pubescence somewhat dense and whitish silver in appearance.

*

Lasius latipes SW, SC, SE, NW, NC, NE

Found in open forests, and fields. Nest in soil, under stones, or at the base of stumps. Hair all over the body is long, numerous and evenly distributed. Queens are easily identified by their unusually thick legs and modest amount of hair all over their body. Hybridization between L. latipes and L. murphyi is one of the rare cases where a hybrid has been given a species name, L. pogonogynus. (Trager, "Advances in Myrmecology:" 405-417) Hybrids between claviger and with colordensis also occur but not enough to be given formal names.

Lasius murphyi SW, SE, NW, NC, NE

Found in open forests, and forest edges. nest in sandy soil under or next to stones. Hair all over body is short. Standing Hairs mostly on propodeum. Queens are orange in color and have yellow fuzz on their face.

Lasius pogonogynus SW, SC, NW, NC, NE

Hybrid species between L. murphyi and L. latipes. Workers are exactly like L. latipes. Latipes has longer hair but that's not saying much. Queens have thick legs of L. latipes but lack the hair on the abdomen. Body hair is otherwise distributed similar to L. murphyi but much longer. This may vary some from hybrid to hybrid.

*

Lasius occidentalis SW, SC, NW, NC

Rarely found. Nest in dry soil under stones. Hairs on face has whisker-like effect occurring under the eyes and along the side of the head. Other Lasius have hair here too but the white color seems unique enough to this species.

Lasius plumoplosus SE, NC, NE

Nest under stones and in rotting logs. Lots of standing plumose tipped body hair.

Lasius pubescens NC (Only found in Minnesota)

Found in open forests. Nest in soil. Hair on Gula. Pubescence all over body.

The End

Sources

Cole, A. C., Jr. 1956a. Studies of Nevada ants. II. A new species of Lasius (Chthonolasius) (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). J. Tenn. Acad. Sci. 31: 26-27

Cole, A. C., Jr. 1958a. A remarkable new species of Lasius (Chthonolasius) from California (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). J. Tenn. Acad. Sci. 38: 75-77

Cover, S.P.; Sanwald, R. (1988) Colony Founding in Acanthomyops murphyi, a Temporary Social Parasite of Lasius neoniger. Advances in Myrmecology by James Trager, 405-417

Wheeler,W.M. The Temporary Social Parasitism of Lasius subumbratus Vierect. Psyche, 24, 166-176

MacKay, W. P.; MacKay, E. E. 1994. Lasius xerophilus (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), a new ant species from White Sands National Monument, New Mexico. Psyche (Camb.) 101: 37-43

Wilson, E.O. (955) A Monographic Revision of the Ant Genus Lasius. Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology, 113, 1-201

Wing M. W. (1968) Taxonomic Revision of the Nearctic Genus Acanthomyops (Hymenoptera:Formicidae). Memoirs of the Cornell University Agricultural Experiment Station, 405, 1-173.

Here is a home made key to Lasius based on information found in the links below. Bare in mind this is my interpretation of the info and I've never seen half of these in person. This is a very common genus of ant that I've decided to focus on because to often people were identifying the ant to subgroup level and accepting that as the species. I feel we can do better then that and chances are one of you may have found something other than the common L. neoniger, L. alienus, L. flavus, L. claviger, or L. umbratus.

Before we begin, I would to offer a special thanks to AntWeb.org and Bugguide.net as I link to both for pictures. Antweb is favored heavily though.

Identifying Lasius is surprisingly difficult. Good magnification is key. Species are broken up into four groups. Niger tend to be dark black brown workers and sometimes amber-orange in color. Flavus, Umbratus, and Claviger all have orange workers, and are almost completely subterranean. Within each group there seems to be a lot of hybridization but this doesn't seem to spread beyond the group they're in.

To determine which group the species is found two traits are vital. The first is the size of the eye compared to the size of the head! The second is the length of the maxillary palp which is located under the head and looks like an antenna. Both need to be viewed with a side view of the head.

This needs to be done to the worker caste. Queens are almost completely different and vary in appearance in some species.

Niger group all have large eyes compared to the head. They also have the longest maxillary palp.

Claviger group have small eyes compared to the head. They also have the shortest maxillary palp. It's said to be 3 segments long which is another way of saying it can not be seen with the naked eye!

Flavus group have small eyes compared to the head (on par with Claviger). They have a short maxillary palp but unlike Claviger it's viable though tiny.

Umbratus group have large eyes similar to Niger group. The maxillary palp is said to be somewhere between Niger and Flavus in length. They are probably the easiest to confuse with the Flavus group.

Hopefully you're still with me. As said before species hybridization tends to be common. What's more some species have subspecies or varieties where the Lasius you thought you knew has something crazy going on like no hair what so ever. You may be wondering if species can simply breed with one anther interchangeably what in the world keeps them pure? I don't have the answers for all the species listed but can offer an example. Lasius neoniger is a common species that nests in fields, prairie, and open grassland areas. Step into the woods though and you start finding Lasius alienus which prefers to nest in logs, tree stumps, or mixed nests under dead wood. Hybrids occur in both forest and field but for the most part they hold their nuptial flights above areas where they would normally nest, thus swarms are mostly separate and they keep their own genetics reasonably pure.

Before moving on it's important to know what a Seta Count is as well a few other things.

Seta Count - The number of Standing Hairs beyond the outline of the following: Anterior Scape Surface as viewed in line with the plane of funicular flexion, and the Outer Surface of the Fore Tibia as viewed in line with the plane of tibial flexion.

Standing Hairs - A hair with subdecumbent, suberect, or erect, i.e. forming an angle with cuticular surface of 45degrees or more.

To determine which group the species is found two traits are vital. The first is the size of the eye compared to the size of the head! The second is the length of the maxillary palp which is located under the head and looks like an antenna. Both need to be viewed with a side view of the head.

This needs to be done to the worker caste. Queens are almost completely different and vary in appearance in some species.

Niger group all have large eyes compared to the head. They also have the longest maxillary palp.

Claviger group have small eyes compared to the head. They also have the shortest maxillary palp. It's said to be 3 segments long which is another way of saying it can not be seen with the naked eye!

Flavus group have small eyes compared to the head (on par with Claviger). They have a short maxillary palp but unlike Claviger it's viable though tiny.

Umbratus group have large eyes similar to Niger group. The maxillary palp is said to be somewhere between Niger and Flavus in length. They are probably the easiest to confuse with the Flavus group.

Hopefully you're still with me. As said before species hybridization tends to be common. What's more some species have subspecies or varieties where the Lasius you thought you knew has something crazy going on like no hair what so ever. You may be wondering if species can simply breed with one anther interchangeably what in the world keeps them pure? I don't have the answers for all the species listed but can offer an example. Lasius neoniger is a common species that nests in fields, prairie, and open grassland areas. Step into the woods though and you start finding Lasius alienus which prefers to nest in logs, tree stumps, or mixed nests under dead wood. Hybrids occur in both forest and field but for the most part they hold their nuptial flights above areas where they would normally nest, thus swarms are mostly separate and they keep their own genetics reasonably pure.

Before moving on it's important to know what a Seta Count is as well a few other things.

Seta Count - The number of Standing Hairs beyond the outline of the following: Anterior Scape Surface as viewed in line with the plane of funicular flexion, and the Outer Surface of the Fore Tibia as viewed in line with the plane of tibial flexion.

Standing Hairs - A hair with subdecumbent, suberect, or erect, i.e. forming an angle with cuticular surface of 45degrees or more.

Scape - Long antenna segment that touches the connects with the head.

Tibia and Femur see here.

Please note this map and the initials for each region. After the species name the initials for the regions the ant is found is listed. If you live right on the boarder then consider including neighboring regions but otherwise only include ants that are found in your region. Ants found in SW, and SC may also be found in Mexico. Ants found in NW, NC, and NE may be found in parts of Canada that touch those regions. Individual states are mentioned in the event an ant has really limited distribution in a region.

Lasius Niger Group

Lasius neoniger SW, SC, SE, NW, NC, NE

This is the most common niger species found in the US. Found in fields nesting in open soil or under stones. Can hybridize with Lasius alienus. Workers tend to be brown in color with dark legs that are evenly colored. Scape and Tibiae are furry. Queens tend to have a velvet like sheen to the abdomen when viewed at certain angles, but this is also found in other Lasius.

Lasius alienus SW, SC, SE, NW, NC, NE

The most common niger species found in wooded areas. Found in forests, nesting in soil, rotten logs, and stumps. Can hybridize with Lasius neoniger. Workers tend to be black with lighter legs, usually yellow in color. Scape is lacking hair. Seta Count is less than 40, usually less than 20 standing hairs. Queens seta count is never more than 10 and is usually 0.

Lasius niger SW, NW, and Eastern Canada

It's unknown how the SW, and NW populations arrived, or did they originated there and spread to Europe and Asia where they're more common? Who knows. The Eastern Canada population only recently arrived from Europe within the last 50 years. (I know this by memory and am still looking for the source.)

Lasius alienus, and L. neoniger are subspecies of Lasius niger. It is found in both forests and fields, they nest understones and in open soil. Workers tend to be black like L. alienus. Scape and Tibiae are furry like L. neoniger. Legs tend to be dark but yellow at joints, however I don't know how consistent this is. Queens are described as being similar to L. alineus but are covered in hair like L. neoniger. (One wonders if the SW, and NW population isn't just a hybrid between L. neoniger and L. alienus in need of it's own species name.)

Lasius crypticus SW, NW, NC

Found in fields mostly but sometimes woodland. Nest under stones. Similar to Lasius neoniger but darker in color. Scape and Tibiae are mostly free of hair.

Lasius pallitarsis SW, NW, NC, Alaska, Most of Canada.

Found in forests and fields, nesting under stones. Amber Brown in color out west but to similar to L. umbratus in the east to rely on color alone. Has an extra tooth on the mandibles if you have a microscope. Scape tends to be free of hair. Legs tend to be lighter in color. Supposedly this species produces an odor but that hasn't been confirmed. What's really odd is the source mentioned the odor and also talked about umbratus species using them as a host. Niger group species aren't known to produce an odor and one would think for such a widely distributed species this would be an easy confirm or deny. They were being called by their former name though Lasius sitkaensis. (Assuming there is a population of them in Canada that produces the citronella odor unlike in the rest of it's range perhaps L. sitkanensis, or another name, should be reinstated for that group?)

Lasius sitiens SW

Found in forests and fields, usually at high elevations between 7000-8000 feet, give or take. Juniper shrubs and dry open places also describes their environment. Nest under stones. These are a subterranean forager (which is odd for the niger group but that's where they are) Eye's can be smaller and L. flavus like (also very odd for the niger group), but the maxillary palp doesn't lie. Scape and Tibiae and for that matter The Entire Body mostly lacking hair.

Lasius xerophilus SW (Only found in New Mexico)

Found nesting in sandy soil with small mounds. Similar to L. neoniger but they have more erect hair on the Tibiae.

Lasius Flavus Group

Queens are niger group-like but are a tiny bit smaller and lighter in color.

Lasius fallax SW, NW, NC

This species isn't as common as L. flavus or L. nearcticus. Found in forest clearings where they nest under stones. Scape and Tibia have hair.

Lasius flavus SW, SC, SE, NW, NC, NE

Found in forests and fields (though I want to say finding them nesting in fields is more typical of Europe where they make mounds too.) nest in soil under stones or fallen logs. Open sparsely covered ground is ideal. Scape and Tibia are reasonably free of erect hair. See paragraph below.

Lasius nearcticus SW, SC, SE, NW, NC, NE

Found in dense woodlands. Nest in moist soil under stones or fallen logs. Thick leaf litter is a must. This is a subspecies of Lasius flavus. Scape and Tibia are reasonably free of erect hair.

Lasius flavus and L. nearcticus are hard to tell apart in the western US. They hybridize with greater frequency out there. This doesn't happen as much in the eastern US. Head to head L. nearcticus tends to have a smaller eye compared to L. flavus who have similar sized heads. Lasius flavus's head also tends to narrow some at the mandibles while L. nearcticus doesn't do as much. Supposidly L. flavus workers are polymorphic and L. nearcticus are monomorphic but I find this to not be true. Perhaps it's more accurate to say L. flavus is MORE polymorphic than L. nearcticus tends to be. This theme of Lasius nearcticus having longer traits (sometimes only by fractions of a millimeter) is consistent, but still makes the two species hard to tell apart.

Lasius Umbratus Group

Queens have a smaller abdomen than Niger and Flavus group. These are social parasites of the Niger group. Some are more select than others.

Lasius umbratus SW, SC, SE, NW, NC, NE

This is the most common and wide spread species in this group. Found in both forests and fields, nests under stones in rotting logs and in rotting stumps. Scape and Tibia are not very hairy. This ant is kind of the default model for four subspecies: minutus, speculiventris, subumbratus, and vestitus. They use Lasius alienus, neoniger, and niger as host species.

Lasius minutus NC, NE

Subspecies of Lasius umbratus. Found in sphagnum bogs, dry forests, or swampy fields. Nests in soil often with mounds or masonry domes. Lots of erect hairs all over the body except for the Tibiae which is mostly free of hair.

Queens supposidly share mimetic coloration with host species Lasius alienus. (Wheeler, W.M. 1917 : 167-176)

Lasius speculiventris SC, SE, NC, NE (New Jersey)

Subspecies of Lasius umbratus. Found in forests and field. Nest under stones and in rotten wood. Abdomen is mostly free of hair. Scape and Legs have lots of erect hairs!

Queens might use Lasius minutus as a host along with other Lasius. This is interesting because L. minutus is itself a social parasite. (Kannowski, 1959b : 138-141 153-154)

Lasius subumbratus SW, NW

Subspecies of Lasius umbratus. Found in forests and fields. Nests under stones and rotting logs. Replaces Lasius umbratus where found? Supposedly Scape and Legs have dense pubescence (thin layer of fuzz) and occasionally standing hairs. Ant Web specimens don't seem to have this though, at least not on the legs. The hairs must be very short if they do.

Lasius vestitus SW, NW

Subspecies of Lasius umbratus. Found in forests. Nests in rotting logs and stumps. Replaces L. umbratus where found. Scape and Tibia have lots of hairs. Abdomen is especially covered with lots of erect hairs!

Lasius nevadensis SW (Nevada) Only found in Nevada.

Found in open forests. Nests either under stones or in exposed soil. Scape and Tibiae have longer hair than L. umbratus. Not as shiny as L. vestitus. Has more hair than L. vestitus but less than L. subumbratus.

Lasius atopus SW (Only found in California)

Nest in soil under stones. The Scape is very long for a Lasius extending well above the head. This is unique enough that that's all you need to know to ID this species.

Lasius humilis SW

Found in open woodland and moist fields. Nest under stones. Is found in what has been described as a mountain meadow. Workers are small and pale colored.

Lasius Claviger Group

Queens are very similar to Umbratus group species but most produce a citronella odor. These are also social parasites of Niger group species.

Because Claviger used to be it's own genus (Acanthomyops) the language of identifying them is a little different. The Dorsum side of the Propodeum (top of the last thorax segment), and the Gula (underside of the head, behind the palp) are the main ones. A side view of the ant is best. Some Claviger species have Barbulated or Plumose hair. Barbulated hair means the hair has lots of barbs poking all along the hair. See the top of this ant's head. Plumose hair is similar to barbulated hair but the majority of the barbs at at the tips or top third of the hair, and the effect is greater. see here.

By far the most common two species found are Lasius claviger and Lasius interjectus.

Lasius claviger SW, SC, SE, NC, NE

Found in forests and fields. Nest in soil, and rotting wood. Different from L. interjectus by having hair uniformly along the dorsum of the abdomen. Different from L. latipes by having less hair under it's Gula. Hybridization with Lasius latipes has been noted (Umphrey & Danzmann, 1998 : 431-440)

Lasius subglaber SW, SC, SE, NC, NE

Subspecies of Lasius claviger. Found in forests and fields. Nest in soil, in or under rotting logs and stumps. Mostly short or very little body hair. Gula is usually free of hair.

Lasius interjectus SW, SC, SE, NW, NC, NE

Found in forests and fields. Nest in soil, under stones, rotting logs, and in stumps. Next to walls of buildings is also noted. Propodeum is very convexed. Differs from L. claviger in that hairs on abdomen fall in rows fallowing the tergites (plates that make up the abdomen). Gula has hair.

Lasius arizonicus SW

Subspecies of Lasius interjectus. Found at high altitudes between 5000-8500 feet above sealevel. Nest understones. Easily recognized by almost completely lacking pubescence (thin layer of fuzz) and having a very shiny body. Hairs are very sparse on legs. Propodeum is very convex.

Lasius californicus SW

Subspecies of Lasius interjectus. Found under stones in mountains at mid levels. I couldn't find exact heights. Body hair is somewhat barbulated and is said to be related to L. colei. This is odd because L. colei isn't considered a subspecies of L. interjectus and yet both have the barbulated hair. Gula and Clypeus has 10 or so standing hairs each. Dorsum of gaster with fair amount of standing hairs.

Lasius coloradensis SW, NW, NC (No pictures found, sorry)

Subspecies of Lasius interjectus. Despite being a subspecies of L. interjectus, I read it's easier to confuse this with Lasius claviger. Workers have more body hair but it's shorter in length. L. claviger and L. coloradensis have divided distribution and are rarely found in the same locations.

Lasius mexicanus Mexico

Subspecies of Lasius interjectus. Found in woodlands at high elevations 7900-9000 feet above sea level. Nest under stones. Pubescence on abdomen is dilute to moderate. Hairs are long! Body is shiny. Propodeum is usually convex.

Lasius bureni NC (Wisconsin) Only Found in Wisconsin.

Long standing hairs on Gula. Shorter hairs on dorsum of abdomen. Said to be brown or "yellow-brown" in color. (If that's possible. They might be referring to the uneven color pattern on the head as seen in antweb's pictures.)

Lasius colei SW Only found in the New Mexico and Arizona area. Very uncommon.

Related to Lasius californicus. Body hair is barbulated. Gula and Clypeus have only 4 to 8 standing hairs each. Less hair on the abdomen than L. californicus.

Lasius creightoni SW (Utah) Only found in Utah.

Pubescence somewhat dense and whitish silver in appearance.

*

Lasius latipes SW, SC, SE, NW, NC, NE

Found in open forests, and fields. Nest in soil, under stones, or at the base of stumps. Hair all over the body is long, numerous and evenly distributed. Queens are easily identified by their unusually thick legs and modest amount of hair all over their body. Hybridization between L. latipes and L. murphyi is one of the rare cases where a hybrid has been given a species name, L. pogonogynus. (Trager, "Advances in Myrmecology:" 405-417) Hybrids between claviger and with colordensis also occur but not enough to be given formal names.

Lasius murphyi SW, SE, NW, NC, NE

Found in open forests, and forest edges. nest in sandy soil under or next to stones. Hair all over body is short. Standing Hairs mostly on propodeum. Queens are orange in color and have yellow fuzz on their face.

Lasius pogonogynus SW, SC, NW, NC, NE

Hybrid species between L. murphyi and L. latipes. Workers are exactly like L. latipes. Latipes has longer hair but that's not saying much. Queens have thick legs of L. latipes but lack the hair on the abdomen. Body hair is otherwise distributed similar to L. murphyi but much longer. This may vary some from hybrid to hybrid.

*

Lasius occidentalis SW, SC, NW, NC

Rarely found. Nest in dry soil under stones. Hairs on face has whisker-like effect occurring under the eyes and along the side of the head. Other Lasius have hair here too but the white color seems unique enough to this species.

Lasius plumoplosus SE, NC, NE

Nest under stones and in rotting logs. Lots of standing plumose tipped body hair.

Lasius pubescens NC (Only found in Minnesota)

Found in open forests. Nest in soil. Hair on Gula. Pubescence all over body.

The End

Sources

Cole, A. C., Jr. 1956a. Studies of Nevada ants. II. A new species of Lasius (Chthonolasius) (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). J. Tenn. Acad. Sci. 31: 26-27

Cole, A. C., Jr. 1958a. A remarkable new species of Lasius (Chthonolasius) from California (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). J. Tenn. Acad. Sci. 38: 75-77

Cover, S.P.; Sanwald, R. (1988) Colony Founding in Acanthomyops murphyi, a Temporary Social Parasite of Lasius neoniger. Advances in Myrmecology by James Trager, 405-417

Wheeler,W.M. The Temporary Social Parasitism of Lasius subumbratus Vierect. Psyche, 24, 166-176

MacKay, W. P.; MacKay, E. E. 1994. Lasius xerophilus (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), a new ant species from White Sands National Monument, New Mexico. Psyche (Camb.) 101: 37-43

Wilson, E.O. (955) A Monographic Revision of the Ant Genus Lasius. Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology, 113, 1-201

Wing M. W. (1968) Taxonomic Revision of the Nearctic Genus Acanthomyops (Hymenoptera:Formicidae). Memoirs of the Cornell University Agricultural Experiment Station, 405, 1-173.

Labels:

Distribution,

Identifying,

Key,

Lasius

Saturday, March 27, 2010

Mason Bees and Bloodroot

Well the mason bees I set free have been hanging around the yard. They're so timid and curious. I swear one even recognized me. It flew around me in a curious manner. I'm still not sure releasing them was the right thing to do now that I know they're an invasive species. We have an awful lot of mason bee species in the US and they're so friendly too. The only way I could see one of them becoming invasive is if they hatched out earlier than all the rest to get prime hole reinstate for a nest. Perhaps parasitic wasps and sawflies don't use them as hosts or are somehow overlooked by woodpeckers which would eat the natives. I haven't found a clear answer yet.

Whatever the case they're bees and thus beneficial pollinators. As I said they're hanging around the house and even with their small size they're easy to spot. They mostly hang around the nesting holes, undoubtedly waiting for females to arrive. The brilliant thing about all mason bees though is they're not bias against certain nectar sources, they just go for the nearest flower source. I'm happy to see in this case one of those sources was the bloodroot I planted.

Whatever the case they're bees and thus beneficial pollinators. As I said they're hanging around the house and even with their small size they're easy to spot. They mostly hang around the nesting holes, undoubtedly waiting for females to arrive. The brilliant thing about all mason bees though is they're not bias against certain nectar sources, they just go for the nearest flower source. I'm happy to see in this case one of those sources was the bloodroot I planted.

Friday, March 26, 2010

Adorable Mason Bees

I tried freeing them a day ago, but it was to cold. The only one to try flying immediately landed on my pant leg and refused to let go. This gave me the opportunity to take pictures of these adorable bees.

After posting these at bugguide.net the ID came back as probably the first sighting of Osmia taurus, imported from Asia and considered invasive. However, there is some question if that ID is correct. Despite this, I'm not about to back their cute little brains in just yet. I noticed these hatched out of the smallest cocoons so we'll see what comes from the larger ones. Unfortunately they probably house the females of the invasive Osmia taurus. Here's a picture I took last year.

After posting these at bugguide.net the ID came back as probably the first sighting of Osmia taurus, imported from Asia and considered invasive. However, there is some question if that ID is correct. Despite this, I'm not about to back their cute little brains in just yet. I noticed these hatched out of the smallest cocoons so we'll see what comes from the larger ones. Unfortunately they probably house the females of the invasive Osmia taurus. Here's a picture I took last year.

Thursday, March 25, 2010

Digger Bees and Ants

Now that it's spring it seems some of our native bees are once again becoming active. Walk along a sandy hill side and you'll likely find the mounds of digger bees. These are also called mining bees, and they're a good sign of sandy, semi-sandy or loam soil. They usually don't nest in clay or gravel.

It's still a little cold for them to really be out. This hill side wasn't very active. I suspect these are the holes to last year's bees and thus filled with emerging juveniles that have yet to mate. Each female after mating digs a one or two burrows over her life time. And can create upwards of 40 balls of pollen. Each ball is given a single egg to become next year's generation.

Here is a mound of Pavement ants, Tetramorium species E, for lack of a better species name. You can clearly see from the size of the grains and nest entrance it wasn't constructed by bees. This species is invasive and more than likely in your front lawn, so I didn't bother with a close up this time.

Here we have the smaller mounds to a much smaller ant, Monomorium minimum. Their common name is Little Black Ant. They're about 2mm long or 1/8th an inch. With a smaller ant comes a finer grained mound. I notice they clear away plant matter from their mounts too. They make multiple nest entrances too but it's all comprised in a small patch.

Small enough to test out the capabilities of my new camera. Panasonic Lumix DMC-ZS3 10.1 MP Digital Camera with 12x Wide Angle MEGA Optical Image Stabilized Zoom and 3 inch LCD (Black) I had a hard time finding this camera after I herd about it from Alex Wild. Target, Best Buy, and Walmart didn't have it! I ended up having to go to a specialty camera and technology store. The sales person was very good at talking me into buying all sorts of stuff for it. I'd say all you need is the camera, memory card, and a second battery. The only downfall so far is it saves Video as an MTS file. Can't just open that with quicktime. But it does comes with software for to upload those to youtube and such. It's a little confusing to use. But the macro is excellent for a camera that doesn't need special lenses.

I had a hard time finding this camera after I herd about it from Alex Wild. Target, Best Buy, and Walmart didn't have it! I ended up having to go to a specialty camera and technology store. The sales person was very good at talking me into buying all sorts of stuff for it. I'd say all you need is the camera, memory card, and a second battery. The only downfall so far is it saves Video as an MTS file. Can't just open that with quicktime. But it does comes with software for to upload those to youtube and such. It's a little confusing to use. But the macro is excellent for a camera that doesn't need special lenses.

Monomorium minimum is fairly common. They mostly nest in sandy soil but can still be found along sidewalks and driveways. They're probably nesting in the decomposed granite laid under neath. These are considered a harvester ant too and likely go for grass seeds. They're a neat ant but I've never had much luck with them in captivity.

It's still a little cold for them to really be out. This hill side wasn't very active. I suspect these are the holes to last year's bees and thus filled with emerging juveniles that have yet to mate. Each female after mating digs a one or two burrows over her life time. And can create upwards of 40 balls of pollen. Each ball is given a single egg to become next year's generation.

They are fairly easy to tell apart from ant hills. The soil has clearly been pushed out in neat, and, assuming it hasn't rained, appears lose and flaky. The entrance is usually perfectly round depending on the size of the bee. They're also very likely found around one another in close proximity where as ant hills are not so much. Usually a diverse array of ants will inhabit such a hill side, each with their own sized entrance hole and mound configuration. Some eliminate the grass around the entrance while others leave it there for example. Also when it's an ant hill it's usually quite obvious from the ant traffic going in and out.

Here is a mound of Pavement ants, Tetramorium species E, for lack of a better species name. You can clearly see from the size of the grains and nest entrance it wasn't constructed by bees. This species is invasive and more than likely in your front lawn, so I didn't bother with a close up this time.

Here we have the smaller mounds to a much smaller ant, Monomorium minimum. Their common name is Little Black Ant. They're about 2mm long or 1/8th an inch. With a smaller ant comes a finer grained mound. I notice they clear away plant matter from their mounts too. They make multiple nest entrances too but it's all comprised in a small patch.

Small enough to test out the capabilities of my new camera. Panasonic Lumix DMC-ZS3 10.1 MP Digital Camera with 12x Wide Angle MEGA Optical Image Stabilized Zoom and 3 inch LCD (Black)

Monomorium minimum is fairly common. They mostly nest in sandy soil but can still be found along sidewalks and driveways. They're probably nesting in the decomposed granite laid under neath. These are considered a harvester ant too and likely go for grass seeds. They're a neat ant but I've never had much luck with them in captivity.

Wednesday, March 24, 2010

They're Alive

They are alive! Or at least one is. It's raining outside so I can't release it/them yet. I have my big box of Knox Cellars Mason Bee Tubes set outside and I want to make sure it's the first thing they see. An issue though is the things I want them to pollinate aren't flowering yet, but I'm sure that will change over the course of this bee's 4 to 6 week lifespan.

Maple trees are the most abundant plant blooming now. What's odd is people always sound surprised to learn that "Maple trees bloom?" It's as if no one realizes what those puffy things covering the branches are, and two weeks later, what that stuff is they're cleaning off their car.

There are a few species of maple tree out there. And I don't know how to tell one from the other. I would assume the Red Maple though has the all red flower. If anyone can explain it in so many words please feel free to comment. Thank you.

Maple trees are the most abundant plant blooming now. What's odd is people always sound surprised to learn that "Maple trees bloom?" It's as if no one realizes what those puffy things covering the branches are, and two weeks later, what that stuff is they're cleaning off their car.

There are a few species of maple tree out there. And I don't know how to tell one from the other. I would assume the Red Maple though has the all red flower. If anyone can explain it in so many words please feel free to comment. Thank you.

Tuesday, March 23, 2010

Some Spring Wildflowers

Two years ago I planted a couple of spring wildflowers around the yard. I was hoping to get these established and reproducing. I think either the harsh winter or the rodent population had other plans though. Most of my Trilliums so far haven't come up this year but a few noted successes give me hope to get everything up and running.

Bloodroot, Sanguinaria canadensis, is one such success. I started with just 3 of these. Last year they all came up, but none of them flowered. I blame squirrels which dug around the plants a lot in search of food. This exposed the roots to the harsh cold and now I'm down to one plant. What's great though is that it flowered, and it's fairly pretty.

It's hard to tell but the petals are slightly pink/purple. It's actually kind of odd because the color seems to be more noticeable at night and during the day when the sun is shining the flower appears white.

It's hard to tell but the petals are slightly pink/purple. It's actually kind of odd because the color seems to be more noticeable at night and during the day when the sun is shining the flower appears white.

Here's the pink slightly purple I was talking about. I'm hoping this plant is self fertile and produces seeds. It's one of our plants that is distributed thanks to ants. Gardeners usually don't like this because we like to plant in rows and ants are more messy. I'll be going for the messy look myself, and I'll be sure to plant some more of these. Increase my chances of catching an ant in the act.

Hepatica is another little jewel I thought I'd lost. I planted four of these initially. And I thought all but 1 died. The little clover-like leaf this plant produces is semi evergreen. It lasts the winter but falls off sometime towards the end of the season. That made this little plant so much harder to spot. I really can't stress enough how tiny and delicate looking this flower is.

I've seen smaller flowers of course but usually they're in clusters. This flower is about a centimeter. Note the hairs all over the stem. Those are to prevent ants from climbing on up and stealing nectar from the flower. I forget weather or not ants are later used to disperse the seeds, but it gives me something to find out later on. What's really great though is that multiple flowers come from the same plant.

And it turns out 2 of the plants survived. The other simply didn't produce a leaf. But it has produced a flower. I'll be planting more of this little jewel around the base of trees and along the moss covered roots.

And it turns out 2 of the plants survived. The other simply didn't produce a leaf. But it has produced a flower. I'll be planting more of this little jewel around the base of trees and along the moss covered roots.

Bloodroot, Sanguinaria canadensis, is one such success. I started with just 3 of these. Last year they all came up, but none of them flowered. I blame squirrels which dug around the plants a lot in search of food. This exposed the roots to the harsh cold and now I'm down to one plant. What's great though is that it flowered, and it's fairly pretty.

It's hard to tell but the petals are slightly pink/purple. It's actually kind of odd because the color seems to be more noticeable at night and during the day when the sun is shining the flower appears white.

It's hard to tell but the petals are slightly pink/purple. It's actually kind of odd because the color seems to be more noticeable at night and during the day when the sun is shining the flower appears white.Here's the pink slightly purple I was talking about. I'm hoping this plant is self fertile and produces seeds. It's one of our plants that is distributed thanks to ants. Gardeners usually don't like this because we like to plant in rows and ants are more messy. I'll be going for the messy look myself, and I'll be sure to plant some more of these. Increase my chances of catching an ant in the act.

Hepatica is another little jewel I thought I'd lost. I planted four of these initially. And I thought all but 1 died. The little clover-like leaf this plant produces is semi evergreen. It lasts the winter but falls off sometime towards the end of the season. That made this little plant so much harder to spot. I really can't stress enough how tiny and delicate looking this flower is.

I've seen smaller flowers of course but usually they're in clusters. This flower is about a centimeter. Note the hairs all over the stem. Those are to prevent ants from climbing on up and stealing nectar from the flower. I forget weather or not ants are later used to disperse the seeds, but it gives me something to find out later on. What's really great though is that multiple flowers come from the same plant.

And it turns out 2 of the plants survived. The other simply didn't produce a leaf. But it has produced a flower. I'll be planting more of this little jewel around the base of trees and along the moss covered roots.

And it turns out 2 of the plants survived. The other simply didn't produce a leaf. But it has produced a flower. I'll be planting more of this little jewel around the base of trees and along the moss covered roots.

Labels:

Bloodroot,

Hepatica,

Spring,

Wildflowers

Monday, March 22, 2010

Book Review: The Family Kitchen Garden

The Family Kitchen Garden: How to Plant, Grow, and Cook Together

By Karen Liebreich, Jutta Wagner, and Annette Wendland.

I found this to be a good guide for anyone interested in growing their own fruits and vegetables. It's written in a simple language and covers most of the basics. A true novice, as in someone who lived in the city all their life, might be overwhelmed with some of the info. But over all I think it's a great place for a young gardener to start out. It's better to have the info than not after all.

The first 51 pages are devoted to defining terms and discusses issues like children in the garden. They discuss assorted soil types, how to improve it, composting and so on. Propagation is covered, namely the difference between seeds, division and cuttings, that sort of thing. So these are all things every gardener should know.

The next 100+ pages are probably the most useful. It's a month by month list of what to plant inside, what to plant outside, what to harvest, what maintenance needs to be done, what fun craft things can be done, and even offers a recipe or two. I haven't tried any of the crafts but they're casual little things I could see people doing. They're geared towards garden things like simple bird feeders and plant labels.

What to plant and when seems to be in order, though this book is based in the UK which strangely enough has a climate more similar to the southern US. For those of you living in USDA growing zone 6 and up I'd say do things a month late. Those of you in zone 4 and up give it two months and so on as conditions allow. They're at least in some sort of an order after all.

Recipes I haven't tried because a lot of them call for things I don't grow, like rhubarb. Most months only have 1 recipe, some have 2; and they all lean towards vegetarian. One has shrimp in it though. To their benefit they all seem easy to prepare, but I feel as if the authors missed an opportunity to really make this book shine. I would have loved if they'd thrown in a few easy to prepare proteins and sauce recipes to show how flexible cooking can be, and how interchangeable some items are on the dinner plate. But this is a gardening book and perhaps that's a topic for another tomb.

The last third of the book is a dictionary of plants. Simple things like apples, borage, mint, tomato, squash and so on are all categorized here. How to grow, how to propagate, what varieties are available (though limited), and what types of pests they get can all be found here. The only notable omission from the normal things we grow seems to be water melon. Corn is found under "S" for Sweet Corn. But what it lacks here it makes up for with some obscure plants like gooseberry, currant, and parsnips. Though they're not really obscure I'd say not everyone is growing them. Fruiting trees are also covered, as are the convenient ways to train the branches so even people with small yards can grow them. Herbs and Flowers (some of which are edible) are the last bit.

So I would recommend this book to a friend or even gift it to a new gardeners.

By Karen Liebreich, Jutta Wagner, and Annette Wendland.

I found this to be a good guide for anyone interested in growing their own fruits and vegetables. It's written in a simple language and covers most of the basics. A true novice, as in someone who lived in the city all their life, might be overwhelmed with some of the info. But over all I think it's a great place for a young gardener to start out. It's better to have the info than not after all.

The first 51 pages are devoted to defining terms and discusses issues like children in the garden. They discuss assorted soil types, how to improve it, composting and so on. Propagation is covered, namely the difference between seeds, division and cuttings, that sort of thing. So these are all things every gardener should know.

The next 100+ pages are probably the most useful. It's a month by month list of what to plant inside, what to plant outside, what to harvest, what maintenance needs to be done, what fun craft things can be done, and even offers a recipe or two. I haven't tried any of the crafts but they're casual little things I could see people doing. They're geared towards garden things like simple bird feeders and plant labels.

What to plant and when seems to be in order, though this book is based in the UK which strangely enough has a climate more similar to the southern US. For those of you living in USDA growing zone 6 and up I'd say do things a month late. Those of you in zone 4 and up give it two months and so on as conditions allow. They're at least in some sort of an order after all.

Recipes I haven't tried because a lot of them call for things I don't grow, like rhubarb. Most months only have 1 recipe, some have 2; and they all lean towards vegetarian. One has shrimp in it though. To their benefit they all seem easy to prepare, but I feel as if the authors missed an opportunity to really make this book shine. I would have loved if they'd thrown in a few easy to prepare proteins and sauce recipes to show how flexible cooking can be, and how interchangeable some items are on the dinner plate. But this is a gardening book and perhaps that's a topic for another tomb.

The last third of the book is a dictionary of plants. Simple things like apples, borage, mint, tomato, squash and so on are all categorized here. How to grow, how to propagate, what varieties are available (though limited), and what types of pests they get can all be found here. The only notable omission from the normal things we grow seems to be water melon. Corn is found under "S" for Sweet Corn. But what it lacks here it makes up for with some obscure plants like gooseberry, currant, and parsnips. Though they're not really obscure I'd say not everyone is growing them. Fruiting trees are also covered, as are the convenient ways to train the branches so even people with small yards can grow them. Herbs and Flowers (some of which are edible) are the last bit.

So I would recommend this book to a friend or even gift it to a new gardeners.

Sunday, March 21, 2010

Mason Bee Cocoons

I could have cleaned these off a little better. These are Mason Bee Cocoons. Last year I had all the mason bee nesting blocks and these are all the cocoons I got from them. As well as some type of moth in the upper right. Anyhow lots of wildflowers started blooming here and that means it's about time to pull these out of the fridge. Yes they were in my fridge, don't worry though they were well sealed and insulated with paper towel in a coffee can. (Nothing like accidentally drinking a cup of hot bug juice in the morning to wake you up.)

I wasn't sure if they survived though so I attempted to remove one from it's cocoon. While holding it between my fingers I scratched at it with a needle. Scared the hell out of me when it started buzzing, vibrating, and then after I'd dropped it, rolled around on the table some. Yep they're alive.

So I'll keep them in this plastic container until I see some fruit trees blooming. Then it's out they go. They're active for about the time when blueberries start blooming.

I wasn't sure if they survived though so I attempted to remove one from it's cocoon. While holding it between my fingers I scratched at it with a needle. Scared the hell out of me when it started buzzing, vibrating, and then after I'd dropped it, rolled around on the table some. Yep they're alive.

So I'll keep them in this plastic container until I see some fruit trees blooming. Then it's out they go. They're active for about the time when blueberries start blooming.

Saturday, March 20, 2010

Lasius claviger Fail

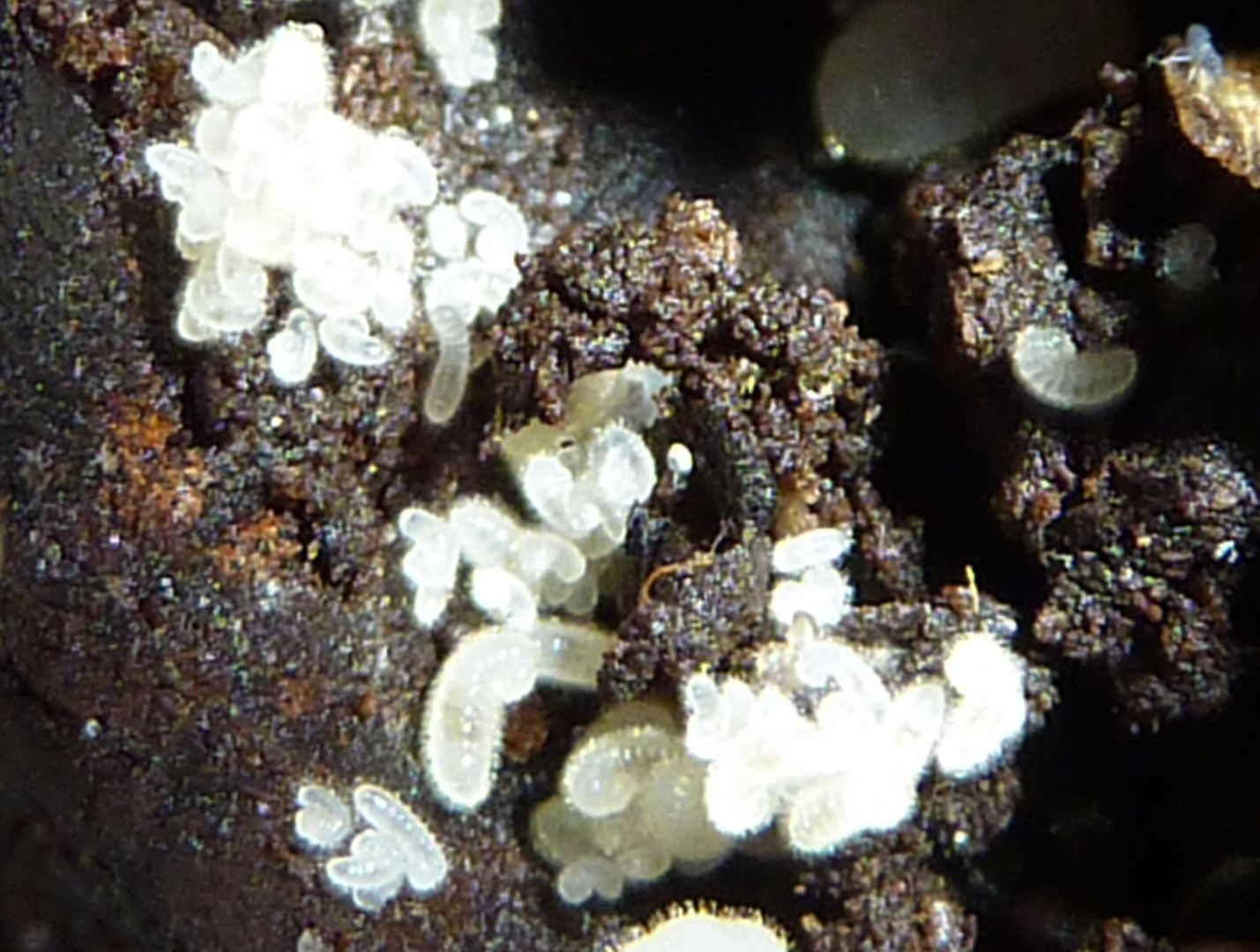

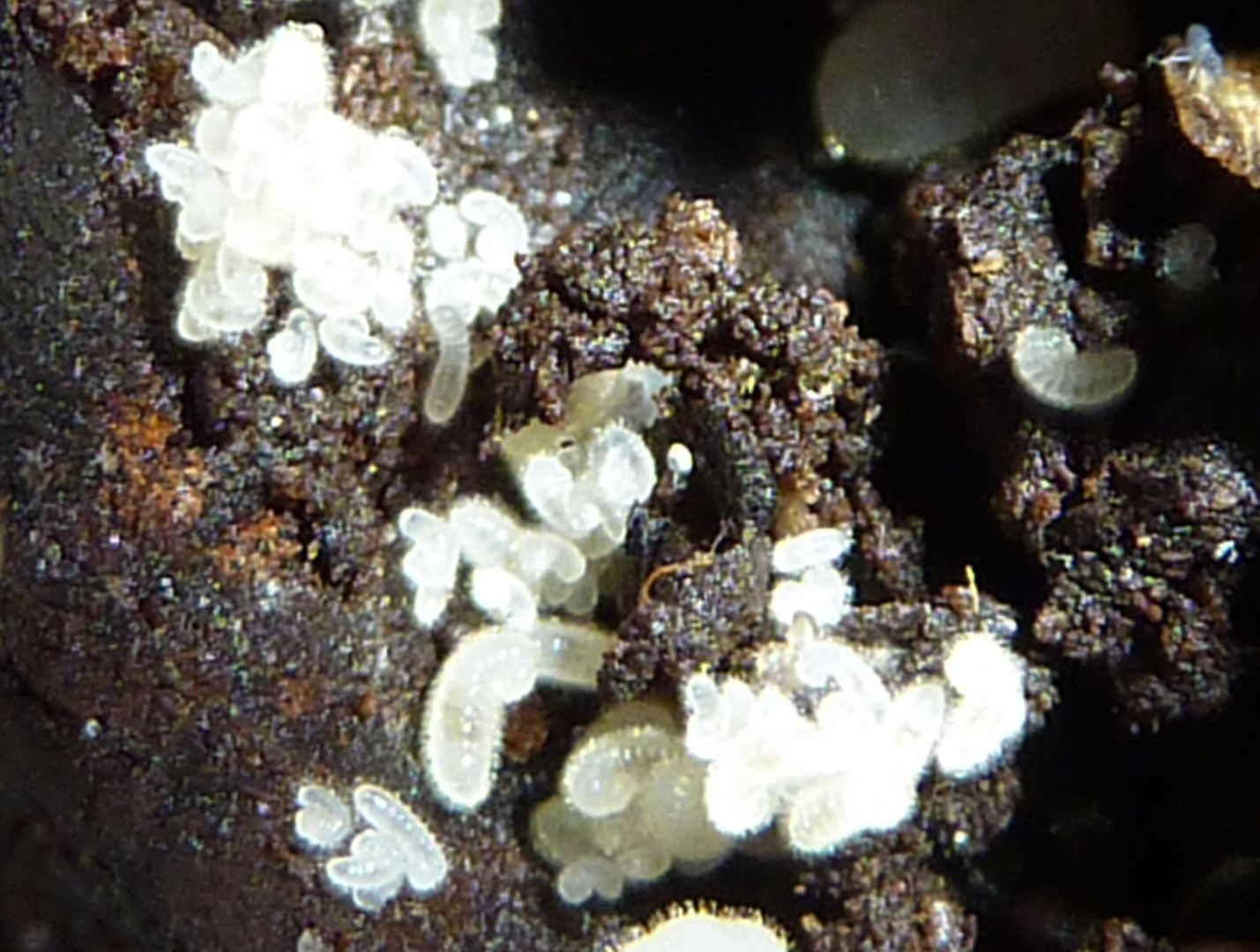

Well spring is here and the parasitic Lasius species are in full gear. Here is the image of Lasius claviger from a few days ago. Earlier today I was out looking for more groups of these about the yard, when I accidentally found a colony of L. alienus. Their log sort of collapsed into my lap and I had the nursery exposed. I'm still getting used to my new camera and wanted to be calm about the colony so my images aren't the best.

This is under the log to the Lasius alienus colony. You can see they have a lot of brood already. But also note the brown/red corpses in the top right and scattered about. These are the graves of failed Lasius claviger queens that tried to take over this colony.

I know one method used by this ant was to play dead and be brought in as food. I don't think this is the case here as many are missing their heads.

This is under the log to the Lasius alienus colony. You can see they have a lot of brood already. But also note the brown/red corpses in the top right and scattered about. These are the graves of failed Lasius claviger queens that tried to take over this colony.

I know one method used by this ant was to play dead and be brought in as food. I don't think this is the case here as many are missing their heads.

Even inside the nest, (just under the bark of the log which collapsed) there are dead queen. Note the eggs scattered about in the background. These were likely brought in as food or executed upon their discovery inside the brood nest.

Lasius alienus larvae (and some other Lasius too) are covered in tiny hairs.

Hopefully accidentally exposing the brood nest to this colony doesn't open the door for more Lasius claviger queens. Lord knows my yard has enough colonies of those as it is.

Friday, March 19, 2010

600 Beekeepers in New York City!

AOL News is reporting New York City lifted it's ban on keeping honeybee hives earlier this week. I've already voiced my opinions on how stupid this is. My argument boils down to central park not providing a year long succession of blooms. Especially when you consider what's said at the end of the article.

Beekeepers who live along the edge might get nectar from the vast suburban area that is as far as the eye can see but there can't be that much there. Homes in this suburban areas are tiny 1 story, probably 3 rooms, with a patch of lawn smaller than the family car. There seemed to be a ban on trees too. While I'm sure some of these homes have flowers, it's hard to imagen them supporting 600 hives.

The article tags something on the end about city beekeepers doing this to be environmentally friendly. They want to help fight CCD.

The environmentally friendly thing for people in the city would be to "green" the city with native plants. This doesn't include lawns. Having to mow the lawn someone planted on top of an 8 story building is stupid and making more pollution than clean air! Lawns are places for people to play, walk, and enjoy the sport of golf; they're well groomed achievements of controlling a highly invasive plant and don't have anything to do with environmentalism other than composting. Lush prairie plants, flowering trees, native shrubs and living walls are what they should be going for. Food crops for humans, and even berry plants for passing birds, would have to be done in raised beds. City soil tends to be teaming with heavy metals.

In a world where Google Maps is taking satellite images of everything, I never understood why companies don't advertise on the roof of their building. A rooftop garden with flowers to form the company logo is an excellent idea in todays world.

If nothing else comes from this I hope that beekeepers of New York demand stricter standards on recycling and help green the city up more with excellent nectar sources. Sadly though beekeepers tend to be part of the problem when it comes to planting invasive like Purple Loosestrife, which are an excellent source of nectar but do awful things to the environments they infest.

There reportedly are about 600 beekeepers in the city.WOW! That number sounds so exaggerated it's hard to believe. To put that in perspective, all of New Jersey has roughly 2,000 registered beekeepers, (give or take 100). Even with our lush underdeveloped areas with assorted blooming flora, we have to rinse out everything that goes into our recycling bin or our hives start dumpster diving for old soda and cat food. I can only imagen what the 600 or so hives are bringing in as "nectar" in the city. A good hive can bring in 100lbs of honey in a year, and foragers travel up to 6 miles away from the hive. I've driven through New York before and there's virtually nothing in the city besides central park.

Beekeepers who live along the edge might get nectar from the vast suburban area that is as far as the eye can see but there can't be that much there. Homes in this suburban areas are tiny 1 story, probably 3 rooms, with a patch of lawn smaller than the family car. There seemed to be a ban on trees too. While I'm sure some of these homes have flowers, it's hard to imagen them supporting 600 hives.

The article tags something on the end about city beekeepers doing this to be environmentally friendly. They want to help fight CCD.

The world is not all bright for North American bees, however, as researchers still struggle with finding the cause of colony collapse disorder, a mysterious syndrome that has been eviscerating bee populations since it was first identified in 2006.My god it's like no one has YouTube or something!

The environmentally friendly thing for people in the city would be to "green" the city with native plants. This doesn't include lawns. Having to mow the lawn someone planted on top of an 8 story building is stupid and making more pollution than clean air! Lawns are places for people to play, walk, and enjoy the sport of golf; they're well groomed achievements of controlling a highly invasive plant and don't have anything to do with environmentalism other than composting. Lush prairie plants, flowering trees, native shrubs and living walls are what they should be going for. Food crops for humans, and even berry plants for passing birds, would have to be done in raised beds. City soil tends to be teaming with heavy metals.

In a world where Google Maps is taking satellite images of everything, I never understood why companies don't advertise on the roof of their building. A rooftop garden with flowers to form the company logo is an excellent idea in todays world.

If nothing else comes from this I hope that beekeepers of New York demand stricter standards on recycling and help green the city up more with excellent nectar sources. Sadly though beekeepers tend to be part of the problem when it comes to planting invasive like Purple Loosestrife, which are an excellent source of nectar but do awful things to the environments they infest.

Labels:

beekeeping,

Bees,

CCD,

city,

environment

Thursday, March 18, 2010

Crocuses Expanding

Two years ago I planted a couple of Crocuses in the lawn. A patch of these flowers came up and it looked nice. Here is a picture of the patch last year.

And here is a the patch today.

Now let's zoom out some.

Most of these I personally planted two years ago and they've been spreading nicely. Squirrels, though, have been digging them up some and replanting them elsewhere. Out front I have a few daffodils planted along the roots to an old cherry tree we have.

They're the tall grass bits and haven't filled in at all, or bloomed yet. But...

Apparently the squirrels decided to plant a crocus out there too.

I have them in patches to make garden boarders. I think it's time I introduced some native wildflowers though.

Natives that I wish had better common names like:

Pussy Toe, Antennaria

Pasque flower, Pulsatilla

Spring Beauty, Claytonia virginica

All of which grow short enough to be planted in lawn area, and bloom about now. I had planted pussy toe last fall but I think the harsh winter did them in. Oh well. I'll try seeding next time.

And here is a the patch today.

Now let's zoom out some.

Most of these I personally planted two years ago and they've been spreading nicely. Squirrels, though, have been digging them up some and replanting them elsewhere. Out front I have a few daffodils planted along the roots to an old cherry tree we have.

They're the tall grass bits and haven't filled in at all, or bloomed yet. But...

Apparently the squirrels decided to plant a crocus out there too.

I have them in patches to make garden boarders. I think it's time I introduced some native wildflowers though.

Natives that I wish had better common names like:

Pussy Toe, Antennaria

Pasque flower, Pulsatilla

Spring Beauty, Claytonia virginica

All of which grow short enough to be planted in lawn area, and bloom about now. I had planted pussy toe last fall but I think the harsh winter did them in. Oh well. I'll try seeding next time.

Wednesday, March 17, 2010

An Innovation in Moving Test Tube Colonies

Alright, the water in your tube is running low. You have to move the colony but the colony is to small to really bother with a larger dirt or plaster setup. What do you do? Move them to a new test tube of course. But the issue is the ants really don't want to move. It's especially difficult if the colony has brood and the eggs are near imposable to get out of the old tube. The issue of course being eggs are to vital to a young colony to lose, but if the ants find their old tube they'll move right back in. I've had this happen dozens of time.

Recently though I discovered an innovation. See what I'd normally do tape the two tubes together (old and new) leaving a small gap for moisture to escape. The gap is so condensation doesn't drown the ants. Well I did this to a colony of Lasius and I made the new tube seem so much more inviting. I made that side completely dark, but still they remained loyal to their mold piece of cotton. I was thinking well maybe they'll just move in a week or two.

A week or two passed and I seriously needed to feed the colony. Before breaking the tape off I had a genius idea. I tipped the colony once again to get them in the new tube. Only the queen and some workers fell though and the bulk of the colony and brood were still in the old nest. Apparently though that was good enough. The week or two the two tubes had spent connected allowed the colony odor or whatever it is that tells the ants "This is Home" was now in both tubes.

This didn't last though, but it was something nevertheless. The queen and workers that fell in the new tube remained calm and didn't bother moving back to the old nest until 3 days later. I can't help but feel that there is something to be exploited in this to get more instant results. Even though the queen has moved back with most of the workers I still see a worker or two checking the place out. Perhaps if I kept the new nest darker than the old one it may have triggered them to stay or move the rest of the colony.

Recently though I discovered an innovation. See what I'd normally do tape the two tubes together (old and new) leaving a small gap for moisture to escape. The gap is so condensation doesn't drown the ants. Well I did this to a colony of Lasius and I made the new tube seem so much more inviting. I made that side completely dark, but still they remained loyal to their mold piece of cotton. I was thinking well maybe they'll just move in a week or two.

A week or two passed and I seriously needed to feed the colony. Before breaking the tape off I had a genius idea. I tipped the colony once again to get them in the new tube. Only the queen and some workers fell though and the bulk of the colony and brood were still in the old nest. Apparently though that was good enough. The week or two the two tubes had spent connected allowed the colony odor or whatever it is that tells the ants "This is Home" was now in both tubes.

This didn't last though, but it was something nevertheless. The queen and workers that fell in the new tube remained calm and didn't bother moving back to the old nest until 3 days later. I can't help but feel that there is something to be exploited in this to get more instant results. Even though the queen has moved back with most of the workers I still see a worker or two checking the place out. Perhaps if I kept the new nest darker than the old one it may have triggered them to stay or move the rest of the colony.

Tuesday, March 16, 2010

Lasius claviger Queens Hibernating

It's hard right now for me to flip stones and logs and not find a Lasius queen. These are usually the social parasitic forms that gather in abundance. Their nuptial flight was last fall. Amazingly they over winter on the surface. The ones pictured above are Lasius claviger, I believe from the abundance of hair. Lasius umbratus queens don't tend to be as hairy.

You can see here I've easily found a few dozen. When the weather warms up they'll venture off separately in search of a host colony, in this case L. neoniger or L. alienus.

You can see here I've easily found a few dozen. When the weather warms up they'll venture off separately in search of a host colony, in this case L. neoniger or L. alienus.

Labels:

claviger,

hibernating,

Lasius

Brood Developing

Well I finally got around to taking a picture of the developing brood. They haven't grown much but I'm sure they'll have made great strides by April, maybe new workers by May.

You can make out the one closest to the queen's head (to the left) is nearly double the size of some of the others. I've started feeding them regularly again but I don't think they've found the food. I'll try forcing it on them later on.

My colony of Prenolepis imparis has been doing almost nothing. These are considerably boring ants in all honestly but I love them because they fly early in the year. Wild colonies are probably holding their nuptial flights in parts of the US that are close to or above 70F.

I didn't notice it at the time but if you look at the worker 2/3rds down on the left side, the one facing the right, she's holding an egg! I've had colonies of these before and they always die off because of a failed batch of brood. I believed their diet focused almost entirely on sugar. This colony as you can see is well fed but I focused on protein just as much.

Here is a little better photo where the egg is easier to spot. Notice the different sized heads to the workers in the middle. That's a sign of a good diet in a colony. Usually larger head size (larger caste in general) early on is a sign of good health. Smaller workers are cheaper to produce but aren't as developed as they could be and that usually means they don't live as long.

I'm also happy to see the queen still has some of her original color. I notice that this seems to fade with time. Younger queens seem brighter in color for this species. The browns are more dull orange, the red thorax is a very soft mix of rose red and salmon which is the best I can describe it. Happy Hunting.

Labels:

Ants,

brood,

Camponotus,

castaneus,

imparis,

Prenolepis

Saturday, March 13, 2010

True Signs of Spring

Well it's not quite the 20th yet but I'm reassured this mystical season I hear of called Spring is on it's way. We had a few days in the high 60's here but the reel feel seemed more like 70F. Ant lovers sure know what that means. Prenolepis imparis nuptial flights. And sure enough I see on BugGuide.net someone found a few queens down in South Carolina. Up north where I am though and even in the mid-west colonies held back some. It's as if they could sense the rain storm, currently going on, and simply refused to fly. I imagen flights will resume once we get clear skies after this storm.

During the warm weather though I did a little digging in the compost pile and I found a family of shrews. These are little blind "rodents" (though I don't think that applies to shrews) that eat worms, grubs, and such mostly underground. I didn't expect to find anything living in my mulch pile other than the colony of Lasius claviger (citronella ants) that held their nuptial flight there last fall. So this was a surprise. I place a disk shaped flowerpot, open side down, over them and recovered it with soil. When the rain stops I'll hopefully find out they were moved elsewhere.

During the warm weather though I did a little digging in the compost pile and I found a family of shrews. These are little blind "rodents" (though I don't think that applies to shrews) that eat worms, grubs, and such mostly underground. I didn't expect to find anything living in my mulch pile other than the colony of Lasius claviger (citronella ants) that held their nuptial flight there last fall. So this was a surprise. I place a disk shaped flowerpot, open side down, over them and recovered it with soil. When the rain stops I'll hopefully find out they were moved elsewhere.

All of the soil I'm using this year to make a large mound for food crops. As in my last post I plan on making my yard have a more edible landscape. A nice mound garden in the yard growing assorted crops is right up that alley. I've laid down cardboard over the grass areas to screen out the invasive grasses. And I'll continue this theme until I have eliminated the back lawn completely. That said I was at Lowes earlier and bought an Edible Garden Pack, containing 225 plants for $20! Two types of Potatoes, Red Onion, Shallots, and Asparagus. Individually these would have been sold for $7 each so that was quite a deal. Also picked a few high bush blueberry varieties. I think it's funny some blueberry packets now have Nutritional Facts on the box the plant comes in. They're really selling this Antioxidants, living forever thing.

Returning inside I find an update on my colonies of Camponotus castaneus. For the longest time they were doing nothing at all. Well today I see the clutches of larva have broken dormancy. The larva purposely stopped developing in November but now that it's March they seem to have started back up. I can tell a few have increased in size which means I should focus on feeding the colonies protein again.

I didn't hibernate either colony, but for the past month their setups have been sitting half way on a heating pad. Temperatures changed from 68F to 75F. Not a lot and honestly I don't think it's what triggered the brood to grow either. A month of 75F should have woken the brood up quicker. If I find colonies out in the wild that have small instars as in this colony in April, THEN I'll say the incubation did it. But for now I'm going to say some sort of internal clock did it.